Between 1939 and 1940, 56 passenger liners, all twin screw vessels with a service speed of at least 15 knots, were requisitioned by the Royal Navy, as armed merchant cruisers. Fitted with rudimentary fire control equipment and surface warning R.D.F. they were generally armed with between six and eight First World War vintage, 6 inch guns. For anti-aircraft defence, they had two, 3 inch guns and an assortment of light and heavy machine guns and a few even had an aircraft and catapult added. The best equipped of them all, HMS Corfu, was fitted with gunnery control R.D.F. and had nine 6 inch, four 4 inch, two 2 pounders, nineteen 20 mm guns and an aircraft and catapult.

By the end of 1941, 15 had been lost and the Admiralty decided that they were too vulnerable for ocean escort work and they began to be withdrawn, although some were kept in commission until much later in the South Atlantic and East Indies. By January 1943, only 17 armed merchant cruisers were left, 6 in the South Atlantic, 8 in the East Indies and 3 in Australian and New Zealand waters. By January 1944, they had been reduced to 8 and by May 1944 only the damaged HMS Asturias remained, laid up in Freetown.

By this time, of the other surviving 40 vessels, 1 had been converted to an escort carrier, 1 to an auxiliary anti-aircraft ship, 2 to Depot ships, 4 to Repair ships, 8 to Infantry Landing ships, 2 to Headquarter ships and the remaining 22, to troopships, an obvious and successful role for ex-passenger liners. The Deport and Repair ships, of which HMS Ausonia was one, were later purchased outright and retained in the post war fleet.

Although the Royal Navy had been using depot and repair ships for centuries, the modern era of the repair ship began with HMS Reliance. Built in 1910 as the mercantile Knight Commander, she was brought by the Admiralty in 1913 and converted into a repair ship. Transferred to the Royal Fleet Auxiliary in 1916, she was sold in 1920 to an Italian shipping line, surviving until 1956, when she was scrapped. HMS Reliance was followed by RFA Princetown, which had been the former German liner Prins Adalbert. Seized at Falmouth in 1914 she had been hastily converted to a repair ship, but her naval career was short lived and after only one year’s service, she was sold to a French Line, renamed the Alesia, she was sunk in September 1917.

In 1929 two newly built vessels, the submarine depot ship HMS Medway and the purpose built, fleet repair ship HMS Resource joined the fleet. During the Second World War, 11 merchant ships were converted into general repair ships, six of which were former passenger liners. These conversions, which typically took about two years to complete, were substantial and irreversible and prevented these ships returning to post-war merchant service.

Heavy Duty Repair Ships

Depot and repair ships performed similar functions but not to the extent that they were interchangeable. Depot ships catered for a flotilla of vessels and in addition to repair facilities they provided a base for personnel, which the smaller vessels lacked. Repair ships were used by the fleet generally for repair work, which the combat units were not able to undertake themselves. As the Second World War progressed, so to did the technical nature of the equipment borne by Royal Navy ships and this resulted in a greater demand for depot and repair ships to service them.

To supplement the Royal Navy’s only purpose built repair ship, HMS Resource, five passenger liners were purchased and selected for conversion. The first ship, Antonia was completed in 1942 (renamed HMS Wayland) and was followed by the Aurania (renamed HMS Artifex), Ausonia, Alaunia and Ranpura. All but the Ranpura were former Cunard ‘A’ Class intermediate liners. (Of the other two ships of the ‘A’ Class, Andania and Ascania, Andania was sunk by U-boat and Ascania was converted to a troop landing ship).

The worldwide nature of the Second World War frequently led to the creation of bases in isolated areas where there was limited or no shore facilities. To prevent encroaching on repair shop space when accommodating the large repair staff required for these repair ships, separate accommodation ships for them to live in were employed. For this reason, the repair ships were seldom operated in forward areas and lead to the acquisition of smaller repair ships received under Lend Lease from the United States Navy, which were totally self-contained units with greater flexibility.

The following description and explanation of the Royal Navy’s Heavy Duty Repair Ships in the Second World War was taken from an article read at the Meeting of the institution of naval Architects in London on the 27th March 1947.

Attention has been drawn to the disability attendant on a fleet having to depend for its maintenance on fixed bases and dockyards. This is a problem now well to the fore in the minds of the naval staffs of those powers whose fleets are required to operate at great distances from home waters, conscious as they are of the destructive power of the atomic bomb on fixed bases. The natural tendency is to move towards the adoption of a floating base to service the fleet units so that they are independent of shore facilities, except in the event of great damage which would, in case render them incapable of performing their duties for a period of several months.

At first sight it may be thought that it is only necessary to equip the ships with rudimentary appliances capable of dealing with a few minor repairs and that perhaps at selected places temporary machine shops should be erected ashore to deal with repairs in a more economical manner. But placing equipment ashore brings with it problems of lighting, water, fuel, accommodation and recreational facilities, which ultimately make the creation of such a temporary base a formidable task and one which may quickly prove valueless as the tide of war moves to another area. The repair or depot ship has the great advantage of mobility and of course has her main services incorporated, so that there is a tendency to put into these ships as much equipment as they can work. The ship is then not only a floating workshop but is capable of being sent to any area to back up the existing supply services.

The necessity for a mobile base first arose in the Crimean War when a fleet repair ship was to be found operating in the Black Sea, whilst the advent of the torpedo boat and later the destroyer and submarine in large numbers necessitated, in their turn, the provision of special units to deal with their peculiar requirements. During the recent war the great mobility of the fleet and the necessity for it to operate at great distances from fixed bases, brought about the evolution of several additional types of vessel largely concerned with the maintenance of the fleet. Amongst these, four main types can be discerned; they are; Repair ships – Submarine depot ships – Destroyer depot ships – Maintenance ships.

The function of a repair ship is to undertake only those repairs due to fair wear and tear and stress of weather to fleets, also to carry out simultaneously on two battleships and two cruisers such after action repairs as would obviate these vessels being sent to a main base. Such a ship was HMS Resource, built in 1930.

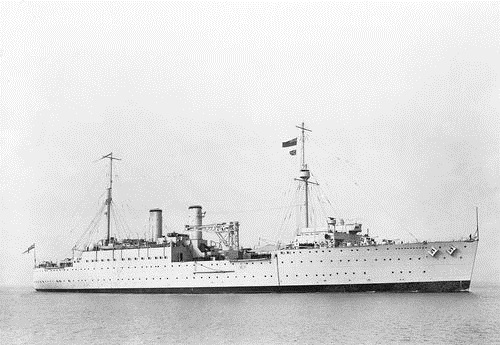

HMS Resource in 1932

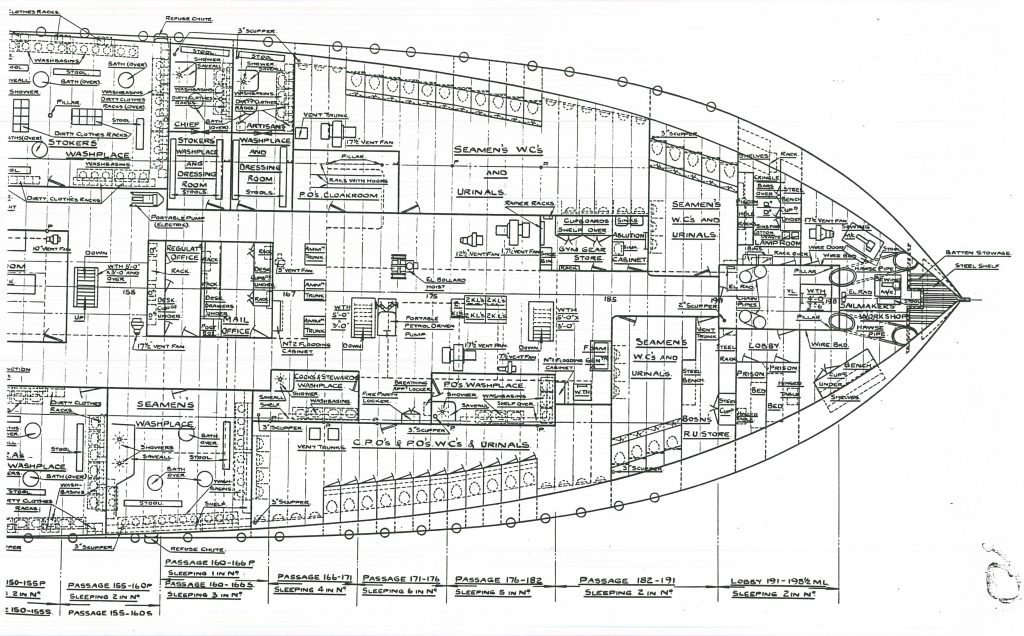

She remained the only vessel specially designed by the admiralty to provide repair facilities afloat for the fleet. Consequently she was termed a “Fleet Repair Ship”. In 1940 it became clear that additional afloat repair capacity was an urgent requirement and a merchant ship, the Cunard liner SS Antonia, was selected for conversion, being completed in Portsmouth in 1942 under difficult conditions. This vessel was renamed HMS Wayland. A feature of this unit and all other conversion undertaken was the introduction of a large quantity of permanent ballast which was fitted for two reasons; firstly to reduce the windage, as it was expected that these ships would have to spend long periods at exposed anchorages and secondly, to adjust the trim so that the vessel could achieve the maximum value from her division, particularly when end compartments were damaged. It was also necessary to increase the electric power fitting three additional 300 kw turbo generators and to augment the freshwater capacity to fitting distillers capable of producing 200 tons a day. Workshops of 37,000 sq ft deck area were provided together with considerable stowage space for naval and workshop stores. To provide the necessary deck height for workshops involved some major structural work, and it was necessary to plate in the ships side over a length of 190 ft., between “B” and “C” decks. Storage tanks for 10,000 gallons of petrol were fitted in a hold compartment with direct flooding arrangements from the sea. In general Wayland’s layout and equipment followed that of Resource, and she had a complement of twenty six officers and five hundred and seventy men of whom about two hundred were actually employed on repairs.

It became apparent however, that Resource and Wayland were although very well balanced as repair ships, larger and more lavishly equipped than was necessary for first aid repairs, yet were inadequate to face the extensive structural repairs found necessary to enable a damaged ship to reach a distant base.

The principal difficulties lay in the lack of plant for producing oxygen and acetylene, insufficient stowage for the large quantities of plates and angles required and in Wayland, the inefficiency of having to use winches and derricks for the rapid handling of stores, it being considered that cranes would be more effective. Both ships, moreover, suffered from the major disadvantage of not having sufficient accommodation to carry a large repair staff.

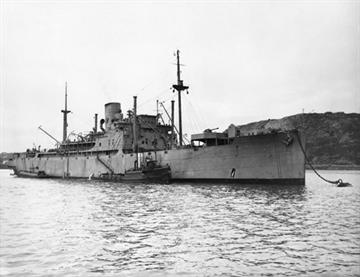

It was therefore arranged to convert four additional vessels into what were termed “Heavy Duty Repair Ships”. These were Artifex (ex-Cunard Aurania), completed at Devonport in July 1944, Ausonia (ex-Cunard), completed at Portsmouth May 1944, Alaunia (ex-Cunard), completed Devonport September 1945 and Ranpura (ex-P&O), completed at Portsmouth January 1946.

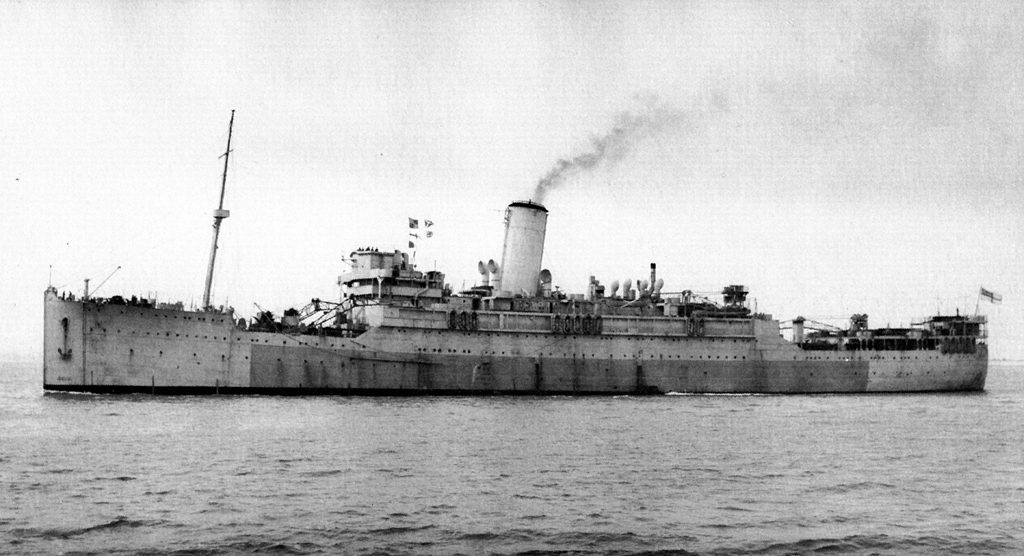

HMS Ranpura in 1946

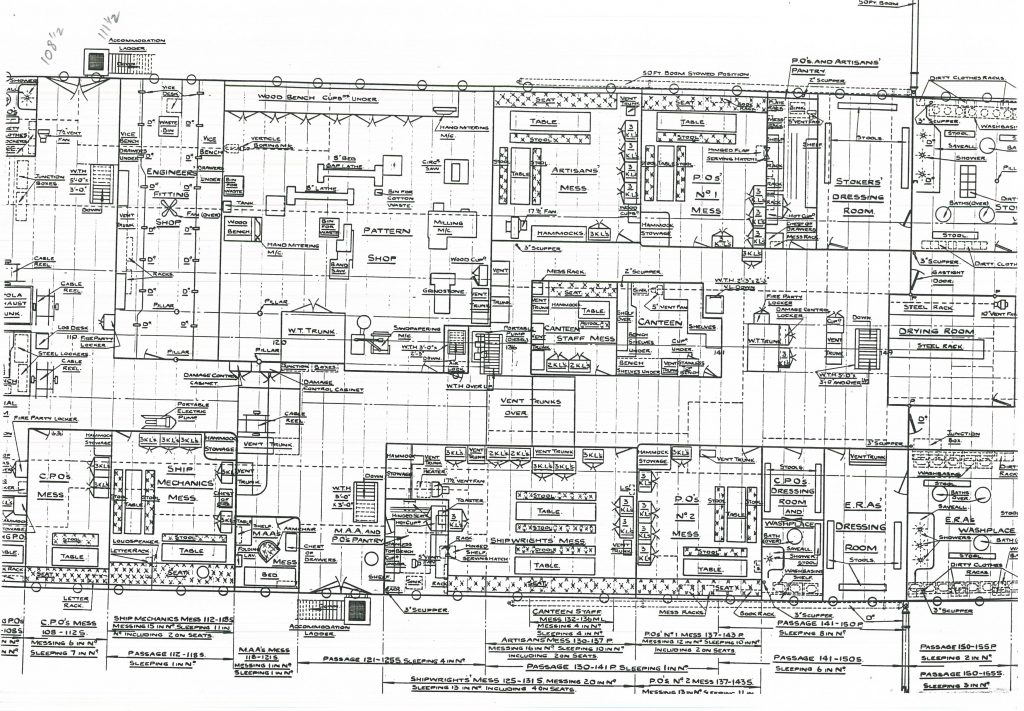

In planning these ships it was necessary to adjust deck heights to suit workshops, consequently portions of “E”, “C” and the promenade decks were completely removed and other flats built as necessary. Care had to be taken to maintain the longitudinal strength by the fitting of additional girders and pillars. In particular, to obtain sufficient ‘tween deck heights for the smithery and plate shops almost all the promenade deck together with its existing pillars had to be removed to allow the new shop to be traversed by the overhead travelling cranes. Heavy middle line pillars were now fitted whilst the deck beams were stiffened by reversed bars to take the increased span. Fore and aft lattice girders were introduced and the side framing between upper and promenade deck was introduced to take the increased racking forces due to the removal of the intermediate deck, which now reduced to a stringer plate heavily reinforced.

The whole was further strengthened by plating in the ship side between the promenade and boat decks over a length of about 220 ft. it was found with the large spaces devoted to workshops and stores that the repair staff could not be increased beyond about two hundred, which was no improvement on Wayland, whereas the workshop facilities were now estimated to be capable of maintaining a working force of at least seven hundred.

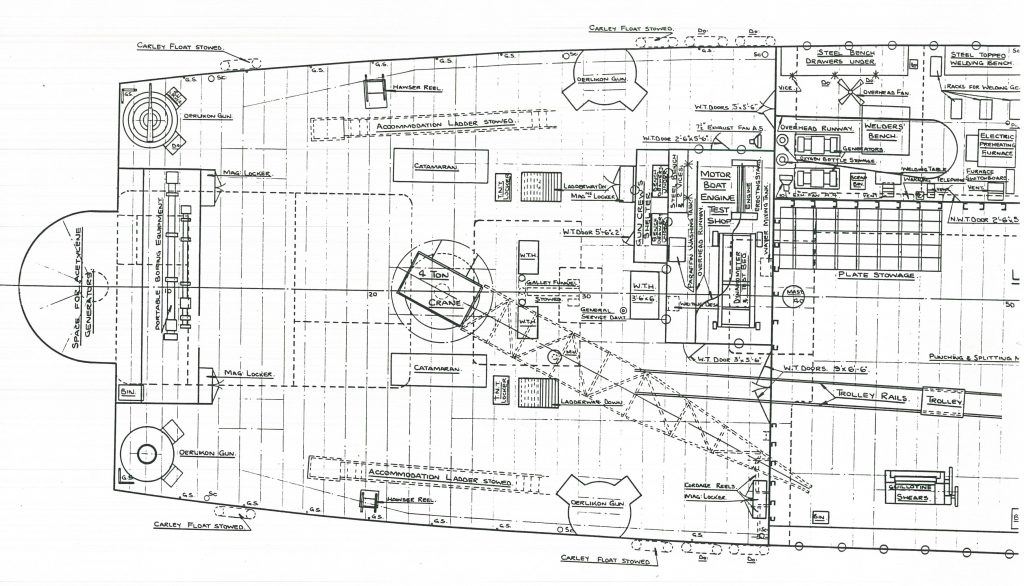

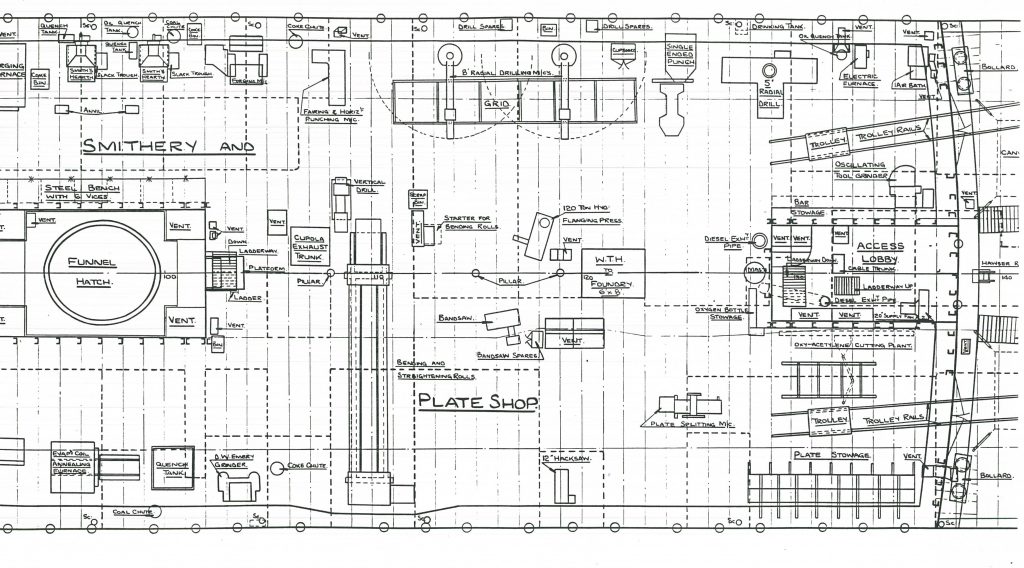

A Deck of HMS Artifex showing the Light Plate Shop and Smithery

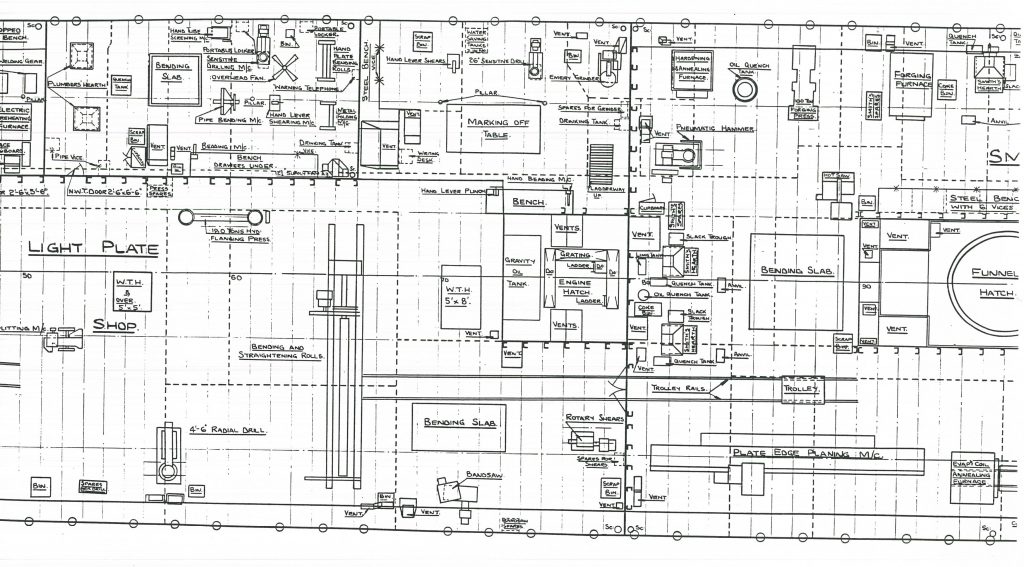

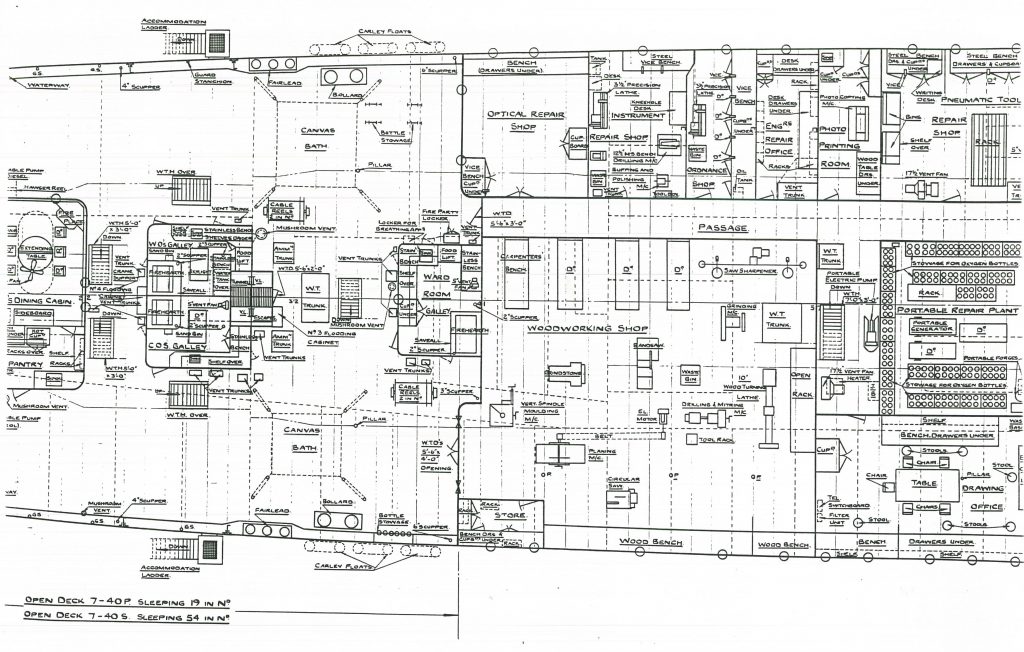

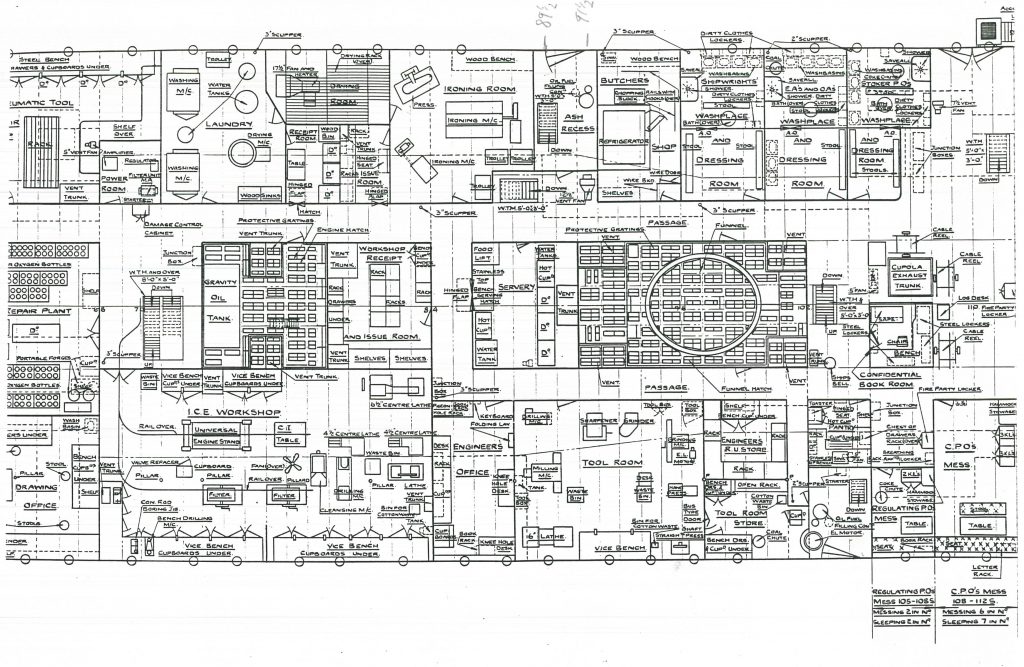

B Deck of HMS Artifex showing the Woodworking Shop, Tool Room and Pattern Shop

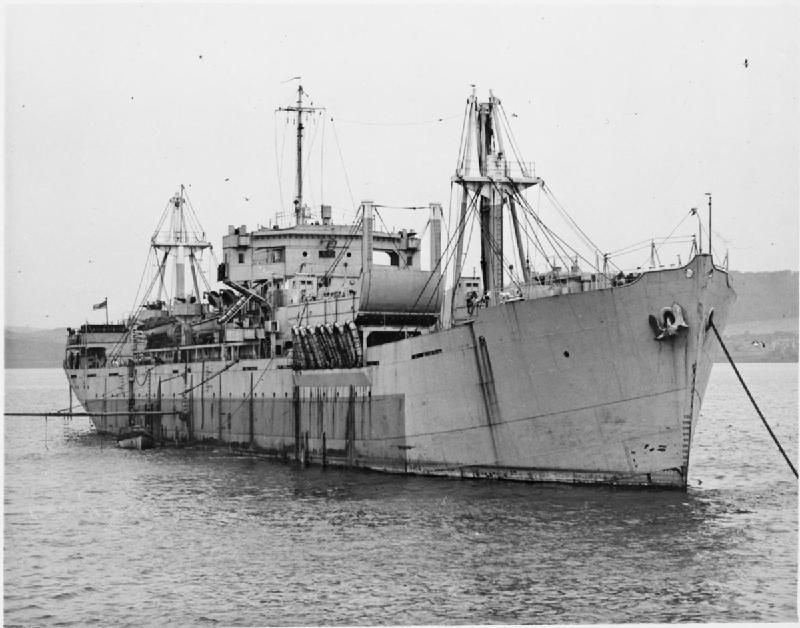

Therefore in 1943 the arrangements to accommodate the extra manpower were reviewed and it was proposed that each repair ship should be accompanied by an accommodation ship, which would carry the five hundred additional staff required. Further, the fall of Singapore had emphasized the necessity for these accommodation ships providing in their extensive holds repair materials of all kinds and spare gear such as watertight doors, hatches, covers, sidelights, stanchions, fans, valves and gearing.

The heavy demand for oxygen also necessitated arrangements being made for its manufacture in all accommodation vessels. Owing to the shortage of merchant tonnage it was possible only to allocate four accommodation ships to the six repair ships; of these SS Lancashire was on station in 1945 and SS Southern Prince arrived later, whilst the remainder never materialised.

HMS Southern Prince

In 1943 it was also thought necessary to back up Resource and Wayland with additional capacity for the undertaking of hull damage repairs and it was intended that each ship should have another vessel in company equipped with a minimum of shipyard machines, together with as much space as practicable for the laying out and working of plates and angles necessary for the repair of hull damage. It was not until 1944, however that two standard P.F.C. types of hull could be fitted out and in the summer of 1945 these became the hull repair ships HMS Mullion Cove and Dullisk Cove respectively.

HMS Mullion Cove

HMS Dullisk Cove

The placing of power driven tools in ships involves much thought, especially in arranging for suitable working space to enable the various operations to be performed. It is to be remembered that in a ship the sequence of operations cannot be planned as at shore establishments, for the work to be carried out is of an uncertain nature. The numerous machines in repair ships, therefore, had to be examined in their merits, particularly such bulky items as bending rolls and if for example, space for both bending rolls and hydraulic press could not be found, the rolls had to go. On the other hand, it was necessary to include both shearing machines as well as oxy-acetylene cutting gear in case the supplies of gas were to fail.

The fundamental workshops required in all repair and depot ships were found to be;

(1) A pattern shop and foundry, capable of dealing with brass and iron castings up to 1000 lb.

(2) A coppersmiths and plumbers shop, suitable for dealing with all pipe work up to 4 inch.

(3) A smithery and plate shop, preferably fitted with pneumatic hammers, forging press, bending slab, anvils, quench tank, plate shearing and drilling machines, bending rolls and acetylene burning facilities, also a light plate section capable of dealing with plates up to ¼” thick.

(4) An electric welding shop, with equipment for about ten welders.

(5) A heavy machine shop, with borers, planners, heavy lathes, gear cutters and milling machines.

(6) A light machine and engineers fitting shop, with radial drills, light lathes, universal millers, and slotting machines, grinding machines, hacksaws, vices and benches.

(7) An internal combustion engine shop, capable of giving complete overhauls to the engines of boats attached to the repair ships.

(8) An electrical workshop, fitted with a hydraulic press impregnator armature-taping machine, coil winders, baking ovens, test switchboard, benches, etc.

(9) A woodworking shop, fitted with a woodworking machine, band saw, planner and jointer, drills and workbenches.

(10) A tool room, fitted with lathes, drills, grinding, hardening, tempering and annealing equipment.

(11) An optical and instrument shop, containing watchmaker’s lathes and benches.

(12) A radar maintenance shop.

To these may be added, when space is available, the following shops; ordnance workshop, asdic workshop, boat repair shop, canvas shop, painters shop, electrical test shop, hydraulic test shop, and a small drawing office.

The main machine shops and smithery should be provided with travellers of capacity up to 4 ton lifts and a plentiful supply of power operated hoists travelling on girders and having 1-ton lifts.

The problem of siting the smithery and plate shop generally proves to be a major problem in converted repair ships. In Ranpura the difficulty was accentuated because she had one superstructure deck less than the earlier ships, therefore, to get the required ‘tween deck height it was necessary to cut away the long bridge deck which of course was a strength deck leaving only a reinforced stringer. The effect of this modification was to lower the top of the strength girder from the bridge deck to the upper deck amidships, consequently the upper deck had to be reinforced by doubling plates so that not only was it strong enough to take the load now thrown upon it, but that the movement of the boat deck above, which was fitted with expansion joints, should be so small that the girders carrying the travellers which were secured to the boat deck would be unaffected. The ventilation problems, which are associated with the foundry situated below decks, need only be mentioned to be appreciated.

It is believed that these heavy repair ships are the foundation of the mobile repair organisation. Their major disadvantage, shown by experience, was the inefficiency caused by the necessity of a daily transfer of hundreds of men to and fro between the heavy repair ship, her accompanying accommodation ship, and the vessel under repair. Therefore, the tendency was to keep the repair ship well back from the main scene of operations where they then found themselves in the company of floating docks.

This created the demand for a smaller type of self-contained repair ship, which was capable of operating close up to the fleet. Two such vessels were received under lease-lend from the USA; they were known as HMS Assistance and HMS Diligence. Each of these vessels carried a repair force of two hundred with the workshop area geared down to the labour force so that its total area was about 16,00 sq ft.

HMS Assistance

A typical example of the work, which can be undertaken by repair ships was that carried out by HMS Artifex on the aircraft carrier HMS Indefatigable, extensively damaged following a suicide attack by Japanese bomber in March 1945. The ship was hit at the junction of the island structure with the flight deck, blowing in the inboard side of the island and extensively damaging the operational equipment and structure in the vicinity. The work of repair was carried out in shifts. As a result of this work being undertaken, HMS Indefatigable was able to remain with the fleet and to operate her aircraft at full efficiency, after one week in hand for repairs, which one would not concede is a very creditable performance and justifies the work put into the production of the fleet repair ship

Extract taken from “The Engineer” newspaper dated the 3rd May 1946

The Repair and Upkeep of H.M. Ships and Vessels in War

By G. A. BASSETT, C.B., R.C.N.C.

Special Arrangements Made for Naval Ships and Craft in Assault Forces

For the North Africa landings in late 1942 the amount of special preparatory work required from shipyards in the United Kingdom on H.M. ships and craft was not great. Whilst a large amount of minor repair work was carried out in the Mediterranean some nine ships were brought to the United Kingdom for permanent repairs and a steady increase in the flow of all types of landing craft into repair ports in this country took place. Special bases, largely employing civilian labour, were set up in the Clyde and other areas, to deal with the maintenance and repairs to minor landing craft and the maintenance of major landing craft.

Prior to the Sicily landings in July 1943, a large number of major landing craft were stiffened for the ocean passage from this country and many modifications to armament and equipment, which were found necessary by experience in the earlier landings, were incorporated.

Although an increasing amount of repair work was carried out in the Mediterranean the numbers of ships and craft being returned from operations in this theatre continued to increase and towards the end of 1943 the strain on the repair resources became greater with the increase of preparations for the invasion of the Continent. It became necessary to institute “follow on” programmes for landing ships and craft in practically every refitting port. The number of landing craft in hand reached a peak value of approximately 300, which was about the maximum number which could possibly be dealt with having regard to the large volume of other important work also in hand. The numbers of landing ships in hand also started to increase owing to the arrival in this country of tank landing ships (L.S.T.) from the U.S.A. and from service in the Mediterranean.

About the middle of 1942, i.e., two years before ” D-Day, consideration was given to the question of provision for the repair of large numbers of landing craft to be used in effecting an allied landing in Western Europe. The docks in the southern dockyards, in the Thames and at Southampton and Falmouth, were needed for the ships concerned and it was evident that landing craft would have to be dealt with by hauling-up slips, tidal grids, etc. In 1942 there were about 220 hauling-up slips in Great Britain and Northern Ireland, of which approximately 120 were situated between Milford Haven and Lowestoft. They were of varying capacities, from small boat slips to slips capable of hauling up a vessel of 1,000 tons.

They were intended to serve ship-form vessels and yachts, and were not suitable for the comparatively broad flat-bottomed major landing craft which require wide cradles.

Designs were prepared for tidal grids and hauling-up slips, both end-on and broadside, for major landing craft (L.C.I., L.C.T., L.C.G., etc.) up to about 500 tons, and for minor landing craft (up to L.C.M.) of about 20 tons. Surveys were conducted on the south coast and suitable sites were selected. Winches and cradles, etc. were ordered.

As a result of two years’ sustained effort, 7 existing slips were converted and 41 new end-on slips, 9 new broadside slips, and 27 tidal S grids were built for major landing craft. 17 existing slips were converted, and 55 new slips and 9 grids were built for minor landing craft.

Provision was thus made to accommodate 165 major and minor landing craft at one time. All these facilities were available by D-Day (June 6, 1944), except that three major slips had not undergone trials.

Special provision was made at these sites for the necessary workshops, stores, washing, sanitation, and canteen facilities, air-raid shelters, etc., plant, compressors and pneumatic tools, welding sets, units of structural, engineering, and electrical material and fittings, and stores including oxygen and acetylene.

The repair labour for these additional slips and grids was provided from local repair firms augmented by about 350 iron workers from northern shipyards. The Royal Dockyards provided the necessary staff to supervise and control the work.

It was decided, as a general principle, that damaged ships and craft which could make the passage were to return from the landing beaches to the United Kingdom for repairs. To patch craft for return to the United Kingdom, the following special equipment was provided: eight sectional floating docks (steel) of 475 tons lift (from United States material); six reinforced concrete floating docks of 400 tons lift.

Special Naval working parties were detailed to operate these facilities in conjunction with special landing craft fitted with workshop equipment. The preparation of the invasion flotillas with their attendant escorts and covering forces made large demands on the Royal Dockyards and commercial shipyards in the United Kingdom.

The U.S. Navy established amphibious bases at Cardiff, Falmouth, Plymouth, Teignmouth,

Dartmouth, Portland, Southampton, and Deptford. These mobile bases were well equipped with workshops and plant. A large part of the preparatory work on U.S. manned landing ships and craft, as well as repairs, was dealt with by the U.S. authorities, and so reduced the load on United Kingdom repair capacity.

The British forces employed in these landing operations in Western Europe were some 700 naval ships, ranging from battleships to tugs, and over 2,000 landing craft of various types. Experience gained during the exercises led to demands for many modifications to landing craft to fit them for special duties in the assaults. Many craft also were damaged during exercises and training. The percentage availability of ships and craft in assault forces on D-day was 97, a result which appeared beyond all hope of attainment during the preparatory period. In this connection it may be of interest to note that one of the battleships employed in these operations was HMS Warspite. This ship sustained bomb damage whilst operating in the Salerno area in September, 1943. Temporary repairs were affected at Malta and Gibraltar Dockyards, and the ship was brought home for permanent repairs. It was not possible to carry out the extensive work required before the commencement of operation “Overlord” and Warspite was brought out for bombarding duties in her damaged condition. The ship sustained further damage (by mine) in June, 1944, and after quick repairs at Rosyth was again brought out for bombardment duties.

Before the repairs on ships and craft engaged in cross-channel operations had materially been reduced, a very large volume of work in preparing landing ships and craft for operations in the Far East had to be undertaken. Because of the continuing pressure on the southern areas this work had largely to be undertaken at northern ports. To give some idea of the magnitude of the work on landing craft it is estimated that in September, 1944, approximately 9,000 men were engaged on about 250 major landing craft throughout the United Kingdom. The work on these craft destined for the Far East included fitting of awnings, cooling machinery, lagging and additional ventilation, in addition to conversions to special types which experience had shown to be necessary. From July 1944 to August 1945, 425 major landing craft had been taken in hand in repair yards and 284 had been completed and sailed from this country.

The projected operations in the Far East also necessitated a large volume of work on landing ships of various types. Approximately 110 landing ships of ten varieties had to be refitted, modified, specially equipped or converted, in order to cope with the arduous duties and climatic conditions in the Far Eastern theatre. With the ships it was necessary to institute a “follow-on” programme, e.g., it was planned to deal with the eighty L.S.T.’s in five batches of sixteen. It is not possible to give a detailed picture of the magnitude of work on these landing ships, some of which are especially built for their duties, and some of which are converted from merchant ship types, but to fit out a L.S.T. occupied some 150 men for about ten weeks, whilst the larger conversion in a L.S.I. would employ anything up to 600 men for several months.

Provision of Repair Facilities Afloat in the Far East

For a war in the Far East it had always been assumed that the main British Fleet would be

based at Singapore and that all docking and repair facilities in the war area, including Hong

Kong and some not under the British flag, would be at the disposal of the Commander –in Chief.

The dockyards at home and those in the Mediterranean, Gibraltar, Malta are sufficiently well known, but it is necessary to point out that east of Malta and round the Indian Ocean and China Seas there were only the dockyards at Simonstown, Singapore, and Hong Kong, and a small storing yard with no repair facilities at Trincomalee. These were then practically the only repair bases for the support of any fleet waging war in the Far East. It is true there was a small dockyard belonging to the Royal Indian Navy at Bombay, and in Australia and New Zealand there were certain facilities for repairs. All these, however, were fully employed in maintaining and repairing their own ships.

In view of the political situation, efforts were made to increase the repair capacity of both Singapore and Hong Kong and by 1941 the labour force at these dockyards exceeded 4,000 and 3,000 respectively. Singapore had a graving and a floating dock each capable of taking all existing warships and a smaller floating dock. There were considerable repair facilities in the commercial shipyards, including a graving dock which could take all cruisers and some aircraft carriers, and four smaller docks. At Hong Kong there was another cruiser dock. The remaining repair facilities in the eastern theatre were on a smaller scale. The nearest capital ship dock was at Durban where repair facilities were small.

The loss of Hong Kong in December, 1941 and Singapore in February 1942, as well as the facilities in the Dutch East Indies, practically the whole of capacity for repairs and docking of the fleet, was a shattering blow. It was necessary to provide a substitute for the facilities lost as soon as possible, in order to ensure the mounting of naval operations.

To provide dockyards or shore repair bases in time was impracticable. It is a long and tedious process to set up repair bases onshore Singapore took fifteen years but as much as possible was done under the very difficult circumstances prevailing in those dark days. Repair facilities afloat had to be organised and whilst ship borne repair facilities had obvious disadvantages, they had the great virtue of mobility, a very great asset in such a far-flung theatre.

When war broke out the Navy had one fleet repair ship, HMS Resource. Immediate action was taken to provide repair ships, with accommodation ships for the Special Repair Ratings (Dockyard), who were specially recruited from the dockyards and shipyards in the United Kingdom to operate these repair facilities. Particulars of the repair ships and associated vessels for which provision was made are given in Table V.

Whilst all these ships were not completed, it is interesting to note that Wayland served at Kilindini, Alexandria, Mediterranean ports, and Trincomalee, Ausonia served at Aden and Manus Island (Pacific) Artifex served at Trincomalee and Leyte Island (Pacific) and Hong Kong. Dullisk Cove had arrived in the Indian Ocean and Mullion Cove was en route to Trincomalee.

There can be no doubt that had the war with Japan continued as was anticipated for, say, another year the facilities provided in the Afloat Repair Organisation would have been fully extended. As it was, those completed rendered most valuable assistance in maintaining the efficiency of the fleet.

Special Repair Ratings

This branch of the naval service was created in June 1942 to assist in meeting the growing demands for manpower required for the repair and maintenance of the fleet abroad. It was impossible to meet the requirements from civilian labour, as volunteers were insufficient to produce the numbers required, and there were no powers of directing men to serve abroad similar to those at home. As men became due for conscription, by age or termination of deferment, those who were considered to have had sufficient experience in a trade or grade required in ship repair work were conscripted, or accepted as volunteers, as S.R.R .s (D). The majority of the officers for the S.R.R.s (D) scheme were volunteers from the civilian officers and men of the Royal Dockyards. They wear uniform but are paid at civilian rates.

The men were sent to the R.N. Barracks at Chatham and vetted by dockyard officers and, if necessary given a trade test before being finally classified. Kitting-up and a five weeks’ disciplinary course followed, and they were then ready for draft. They wear the uniform of petty officer, leading rating, etc. Every trade in the ship repairing industry is represented.

There are some 70 grades in all, ranging from riggers to electric wiremen, and the men are co-ordinated as far as possible to the equivalent grade of general service rating. The .R.R.s (D) were the skilled nucleus of the Repair Party and they were to be assisted by ships’ staffs, and such local unskilled labour as could be used. Apart from being employed in repair bases or repair ships at their own trade, S.R.R.s (D) are in all respects treated as general service ratings. They are not and will not be employed in civil establishments to displace civilian workmen, and are treated as a self-contained body with their own officers and workshops.

The present strength of the S.S.R.s (D) organisation is just over 9,000 officers and men, but the inherent difficulties of working afloat severely limit the extent and volume of work which can be undertaken by them. Large repairs therefore must be carried out at rear bases or in one of the dockyards. There is a great demand for the services of S.R .R .s (D); their job is unspectacular and often arduous, but they have done some excellent work at extremely out-of-the-way places.

Coastal Forces

Special arrangements had to be made for the upkeep and repair of the coastal forces craft distributed around the coast. These craft had been built mainly by yacht and boat-building firms, and the repairs were carried out by these and some of the smaller repair yards. In all, some 90 separate yards were used in the United Kingdom for this work. These yards recruited personnel as necessary; including suitable men for the installation and minor repair of main engines, wireless, etc. and the personnel was often increased by 200 per cent.

Naval depots were set up for the main engines, spare gear, etc., and these greatly assisted with the speeding up of repairs. The Admiralty supplied new slipways and modified others to meet the special needs of these craft. The magnitude of the effort put forward by the firms concerned which, in the main, had previously little, if any, experience of naval work, and certainly no knowledge of the engineering and electrical problems involved, can be judged from the fact that of a total of approximately 500 craft some 120 were usually in hand at one time for repairs of 10 days or more duration. These same firms also repaired a large number of service motor-boats, auxiliary harbour craft and, in some cases, landing craft. One yard, which had large slips available, repaired the following between September 1939 and August 1946:-

Trawlers…………………….23

Drifters………………..72

Coastal craft…………..369

Motor-boats……………48

Motor minesweepers…..6

Landing craft………….103

Steam yachts………….15

Motor patrol vessels…..116

Motor fishing vessels…10

In addition, this particular yard built a large number of small craft and b oats of all types. A tribute must be paid here to the officers and men of these coastal craft who brought the ships to port on many occasions only with very great difficulty. In one instance, M.L. 195 arrived at Grimsby in the early days of 1942 having been damaged by a mine. On arrival, in tow, her forecastle head was 10 ft. below water, and the waterline across the deck abreast the funnel. She was beached and drained, partially plugged, refloated and placed on one of the slips of Messrs’ Doigs, where practically a now fore end was built on.

Conclusion

The foregoing account outlines the demands made on the Royal Dockyards and private shipyards in the United Kingdom in the build-up, repair, and maintenance of the various fleets and forces required for naval operations during the war. When the end of the German war was in sight the naval repair load on United Kingdom resources was almost at its peak. There were some 1,065,000 tons of warships, including 500,000 tons of the larger ships, cruisers, and above, in hand or awaiting repairs in January 1945. During December 1944 over 90 destroyers and escort vessels were in hand as compared with an average of 75 during the previous six months. This included refits of ships due to join the Eastern Fleet, also landing ships and craft for special assault forces in the East.

The large volume of merchant ships in hand in the United Kingdom for repairs at the end of 1944 caused considerable concern, and instructions were issued to curtail naval refits and repairs so as to release men for merchant ship repairs. There has been a steady reduction in the load of naval repairs, and it is anticipated that by, say, mid-1946, all the major refits of H .M. ships will be dealt with in the Royal Dockyards. It is desired to place on record the assistance which has been given to the Emergency Repair Section by the Naval Staff and Admiralty departments generally. Decisions had to be arrived at quickly so that a damaged ship could be instructed as to her repair port. Continuous contact was maintained, by day and night, with the Flag or Naval Officers-in-Charge of the various ports and local repair Overseers, and as a general rule the repair instructions were sent out to the ship within a few hours of notification of damage. Only by the most willing cooperation of all concerned could such a result have been achieved.