The Origins of Merchantmen Camouflage

From virtually the beginning of the age of steam at sea, merchant passenger vessels have been appropriated during times of war to perform auxiliary duties in support of armed forces. In this work they have served their countries needs throughout these periods of adversity as dutifully and successfully as they served those served those of international trade and travel in more halcyon times.

Indeed, ocean passenger ships have proved to be so suitable for emergency work, with their vast and readily adaptable accommodation spaces and high speeds, often superior to contemporary warships, that in wartime they have been converted to serve in many very different capacities as troopship, auxiliary cruisers, hospital ships, commerce raiders, accommodation ships and aircraft carriers, as well as in a number of even more specialised roles.

But for all their suitability, passenger liners were never intended to endure the rigours of sea warfare. As far as is known, none have ever been constructed with armour plating, anti-torpedo bulges or any other structural features which might have afforded them a measure of protection from attack. Even those vessels built with government subsidies are designed with auxiliary employment in mind lacked all but some hull stiffening and deck reinforcement for a number of gun emplacements and perhaps, a slightly superior standard of hull subdivision.

Possibly the only inherent attribute of the merchant passenger liner which has contributed to its well being during wartime was the high speed which peacetime competition on the worlds passenger routes had invariably demanded of it. Whereas the award of a Blue Riband trophy may have represented a nebulous form of prestige in commercial terms, the knots which granted that acclaim assumed a far greater significance when they provided the means to outstrip an enemy submarine.

In recognition of the vulnerability to attack of the majority of passenger ships and other merchantmen called up for war service, some means of concealment was regarded as essential for their protection. Increasingly, they had their commercial livery obscured in order to render them, like warships, less conspicuous on the high seas, a measure that was relatively simple to implement.

Initially, this was achieved by the application of an overall coat of grey paint of some shade or other, a colour that was both cheap and plentiful and easy to apply. On the face of it such a measure of camouflage appeared to be effective enough in practise. Certainly it was as effective as any static method of protection was expected to be and it was generally considered adequate. However, following the outbreak of World War I, the first conflict in which ships were subjected to attack by submarine on a large scale, the progress of the war at sea soon indicated otherwise.

By mid 1917, allied shipping losses were at a critical level as a result of Germany’s policy of unrestricted submarine warfare, threatening the collapse of the entire war effort. This grave situation was a result of much more than ineffective camouflage and to bear this out, the introduction of convoy practises had an immediate impact on the situation. But without question it had also demonstrated that a coat of plain grey paint was invariably an inadequate form of concealment for unarmed merchantmen, whether sailing alone or in convoy.

The achievement of effective camouflage at sea was not easy, being fraught with unique problems. The constantly changing appearance of the environment in different circumstances of light, atmosphere and weather rendered the development of an all purpose concealment measure an impossibility.

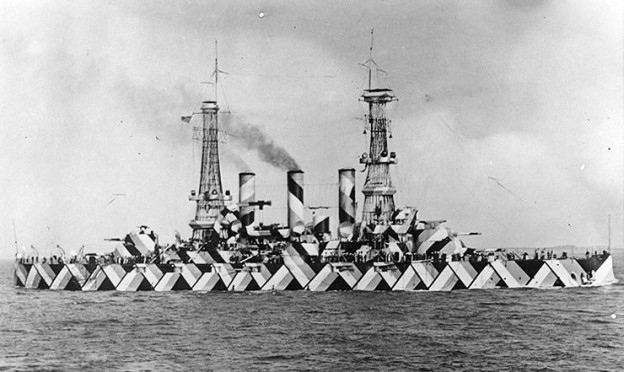

However, necessity being the mother of invention, there was no shortage of suggestions as to how the shipping losses could be reduced by improving maritime camouflage techniques. The Admiralty therefore established, through the Directorate of Naval Equipment, a special section to investigate and implement these ideas. Soon after, following the British lead the United States navy Department’s Bureau of Construction and Repair also set up a Camouflage Research Centre. Its brief was to conduct research into alternative, more effective colour schemes, the objectives being either to reduce target visibility or to confuse target indent and heading. The result of all these actions was a range of innovative and often striking camouflage schemes, launching what in effect was a new art form and completely new school of scientific research.

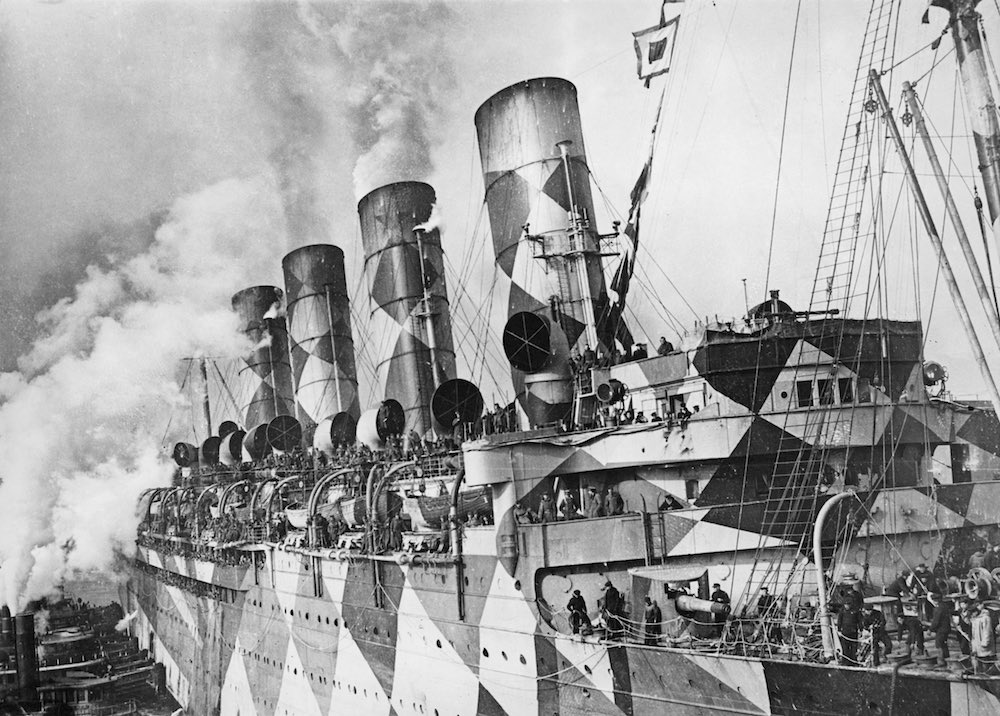

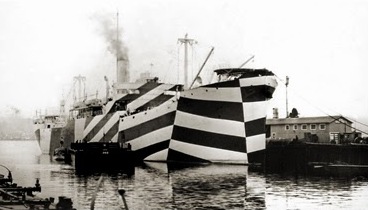

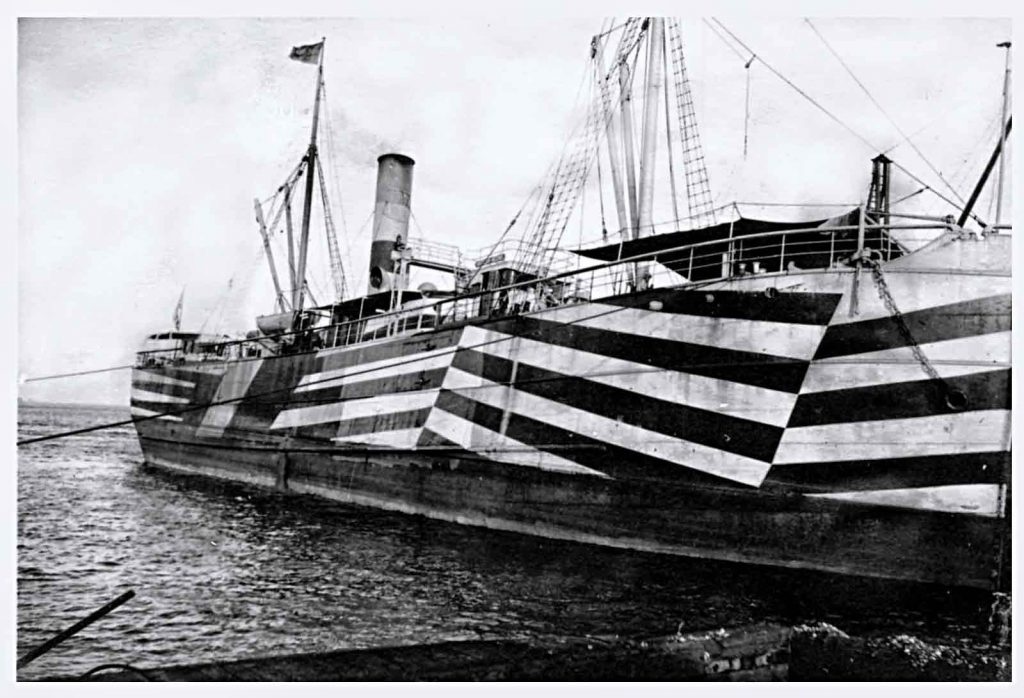

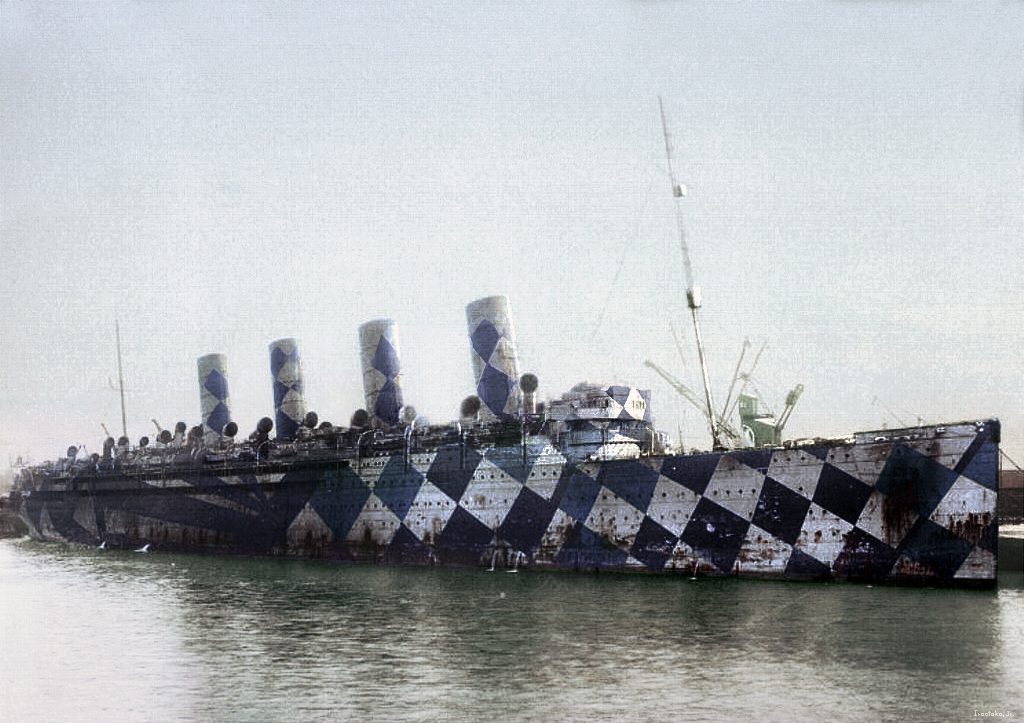

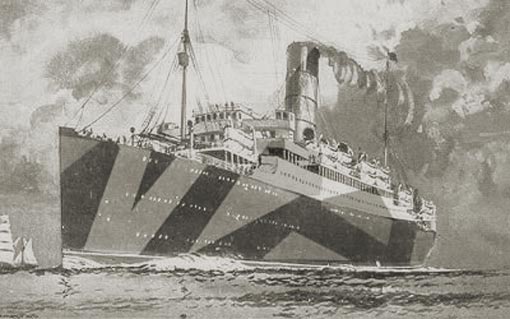

One group of schemes advocated soft hues and subtle textures, with the emphasis on precise colour blending, to create an optical illusion simulating invisibility. Others proposed dazzle painting, as it became popularly known, which called instead for ships to be painted in bright, contrasting colours in strong geometric shapes to make it difficult for a submariner to determine their bearing, speed or identity.

The teams of camouflage advisors assembled on both sides of the Atlantic comprised both artists and scientists and their approaches to the problem reflected the diversity of their backgrounds. One school of painters examined camouflage in the natural world and sought to apply the principles of protection in animal and plant colouring to these mechanical objects. More fundamentally, the scientific fraternity sought a deeper understanding of the very concept of visibility as a basis for devising methods by which it could be manipulated or distorted. Their studies led to the formulation of the first methods of quantitative measurement of visibility and comparative assessment of the effectiveness of camouflage measures.

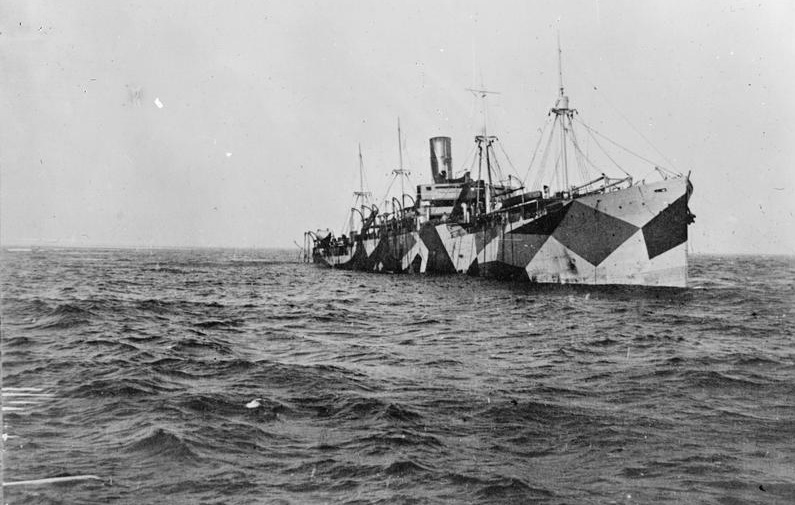

The first HMS Ausoina, seen here sinking after being torpedoed by the German U-boat U-62 on the 30th May 1918, 600 miles out in the Atlantic Ocean. This unique photograph shows another variation of the dazzle paint scheme adopted towards the end of the First World War.

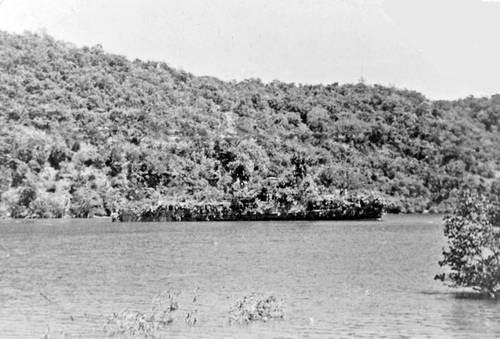

From these early experiments numerous, highly sophisticated and carefully devised disruption patterns were subsequently developed, providing the basis for the camouflage tactics that were adopted during World War II. Painted disguise or concealment was known as static camouflage. Dynamic camouflage or the alteration of a ships appearance by the addition, modification or removal of masts, funnels and other physical features, was also employed as an extension to painted deception in a further bid to outwit enemy submarines and surface raiders.

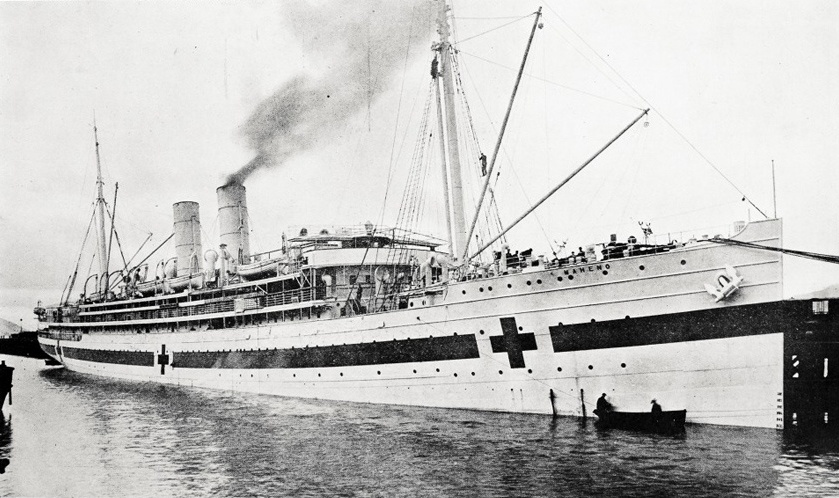

World War I also saw the introduction to certain passenger ships of paint schemes that were intended to achieve the opposite effect of concealment or confusion. As approved schemes under the Geneva and Hague Conventions they were designed both to enhance the visibility and aid the identification of special categories of vessel. On both the one hand, there were the neutrality markings of ships of non-belligerent nations attempting to go about their lawful, commercial business and on the other, there were the colour schemes applied to passenger vessels engaged on duties under the auspices of the International Red Cross, such as hospital ships and later diplomat repatriation ships.

No other group of ships was painted in so many different wartime colour schemes, some individual vessels having received as many as three, four or five changes of livery. For instance, Cunard’s record breaker Mauretania was painted in three different colour schemes during World War I. Another Cunarder, Aquitania, which saw active service in both World Wars, had her appearance altered no less than five times in the course of her auxiliary career, while the British troopship Olympic and the American troopship USS Louisville were certainly not unique in having more than one camouflage scheme tried out on them experimentally during 1917 and 1918.

From an official point of view, the painting of converted passenger ships in protective colouring was deemed to be especially vital. Of all merchantmen, the Admiralty gave the highest priority for camouflage painting to Armed Merchant Cruisers and troopships. Following Americas entry into World War I, the Bureau of War Risk of the Treasury Department also considered it essential for all US registered merchant vessels entering into the war or submarine danger zones to be camouflaged but, due to the enormous number of vessels involved, an order of priority had to be established. This gave precedence to troop transports over all other types of ship.

HMS Ausonia Camouflage

The interwar years found ships of the Royal Navy wearing one of four different paint schemes depending upon which command they were attached to. For vessels of the Home Fleet, the colours were Home Fleet Dark Grey. Ships of the Mediterranean Fleet wore an overall light grey (named Mediterranean Light Grey) as did those serving on the West Indian and South American stations. Vessels attached to the Indian Ocean were usually painted overall white, while ships of the China and Far East commands had white hulls and upper works with buff funnels.

The outbreak of World War II in September 1939 saw no immediate change to ship’s colours and it was not until several weeks later that some of the Home Fleet’s ships began to adopt an overall medium grey colour as being more useful for concealment purposes.

In January 1940 the destroyer HMS Grenville became the first Royal Navy vessel to display a camouflage scheme. Most of the early patterns were generated unofficially, and competitions were often held between ships for the best camouflage patterns. The RN camouflage department experimented with several dazzle pattern variations and decided on a scheme devised by Peter Scott, a naturalist. These schemes were eventually developed into the Western Approaches Schemes.

At least one, former Cunard A Class liner adopted an experimental dazzle pattern scheme when first converted to an Armed Merchant Cruiser. I have been unable to find any photographic evidence to confirm this, but this line drawing of HMS Andania shows how she appeared in June 1940 at the time that she was torpedoed.

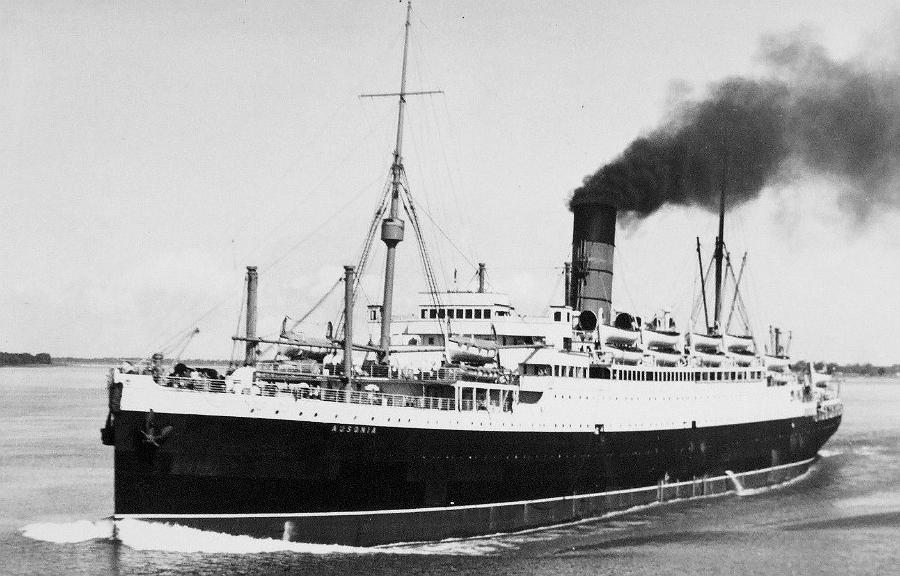

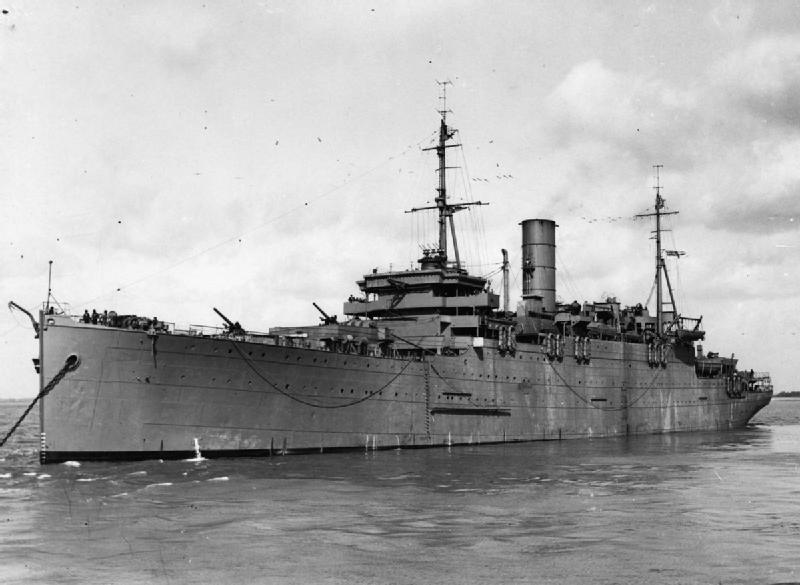

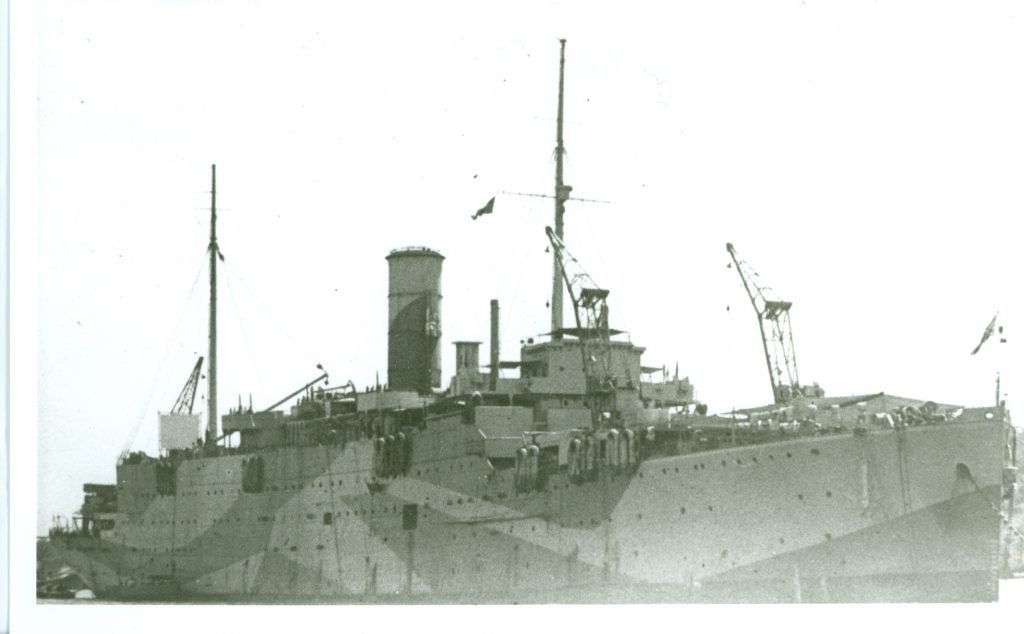

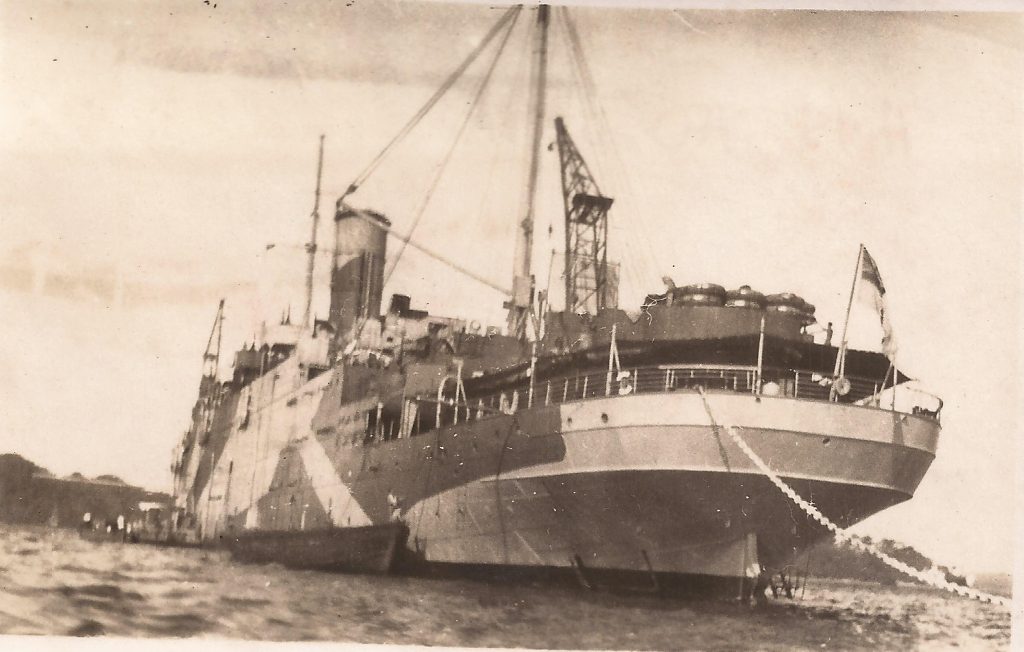

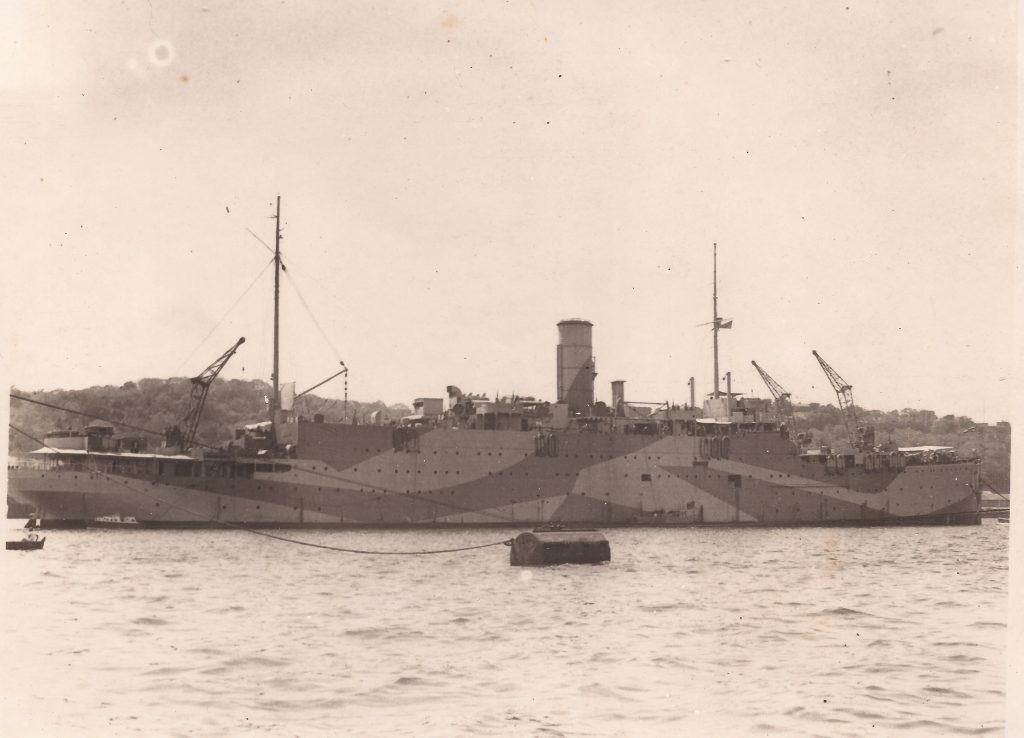

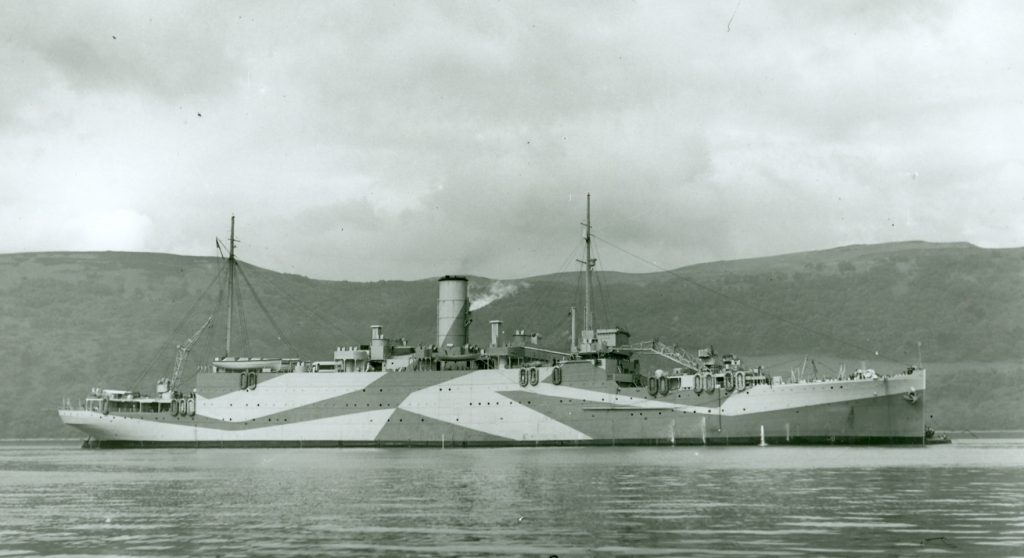

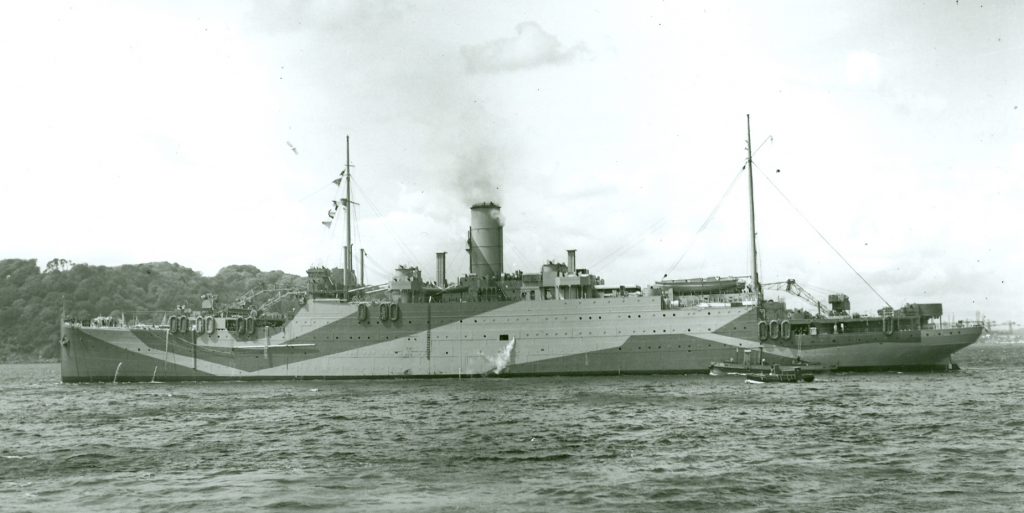

The Ausonia does not seem to have adopted a dazzle pattern camouflage scheme when she was first requisitioned by the Admiralty for conversion into an Armed Merchant Cruiser. Instead her standard Cunard paint livery of black hull and white upper works was replaced with a new two toned camouflage scheme of dark black grey hull with light grey upper works. This scheme had just been introduced by the camouflage section of the Royal Navy and both HMS Ausonia and HMS Aurania were one of the first ships to adopt it.

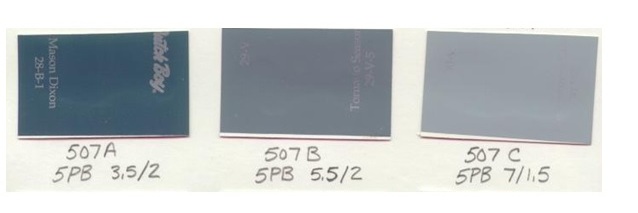

By late 1940 the experimental dazzle patterns adopted by many of these vessels had been replaced with an overall medium grey (507B) scheme. A number of larger warships (cruiser size and larger) did continue to carry camouflage, usually a Modified Peter Scott scheme, using medium grey (507B) and white, with a dark black grey (507A) sometimes being used, but by the summer of 1941, these ships began to adopt the First Admiralty Disruptive schemes, which were used sporadically until the latter part of 1942.

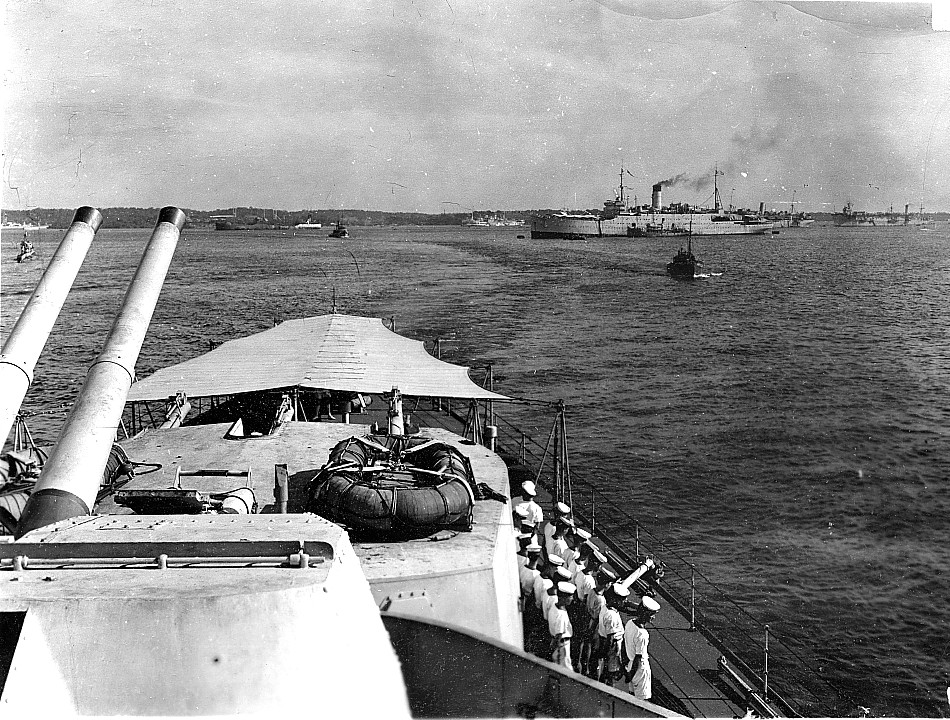

Two former Cunard A Class liners, HMS Alaunia and HMS Antonia can be seen in these photographs with the Home Fleets overall medium grey (507B) camouflage scheme.

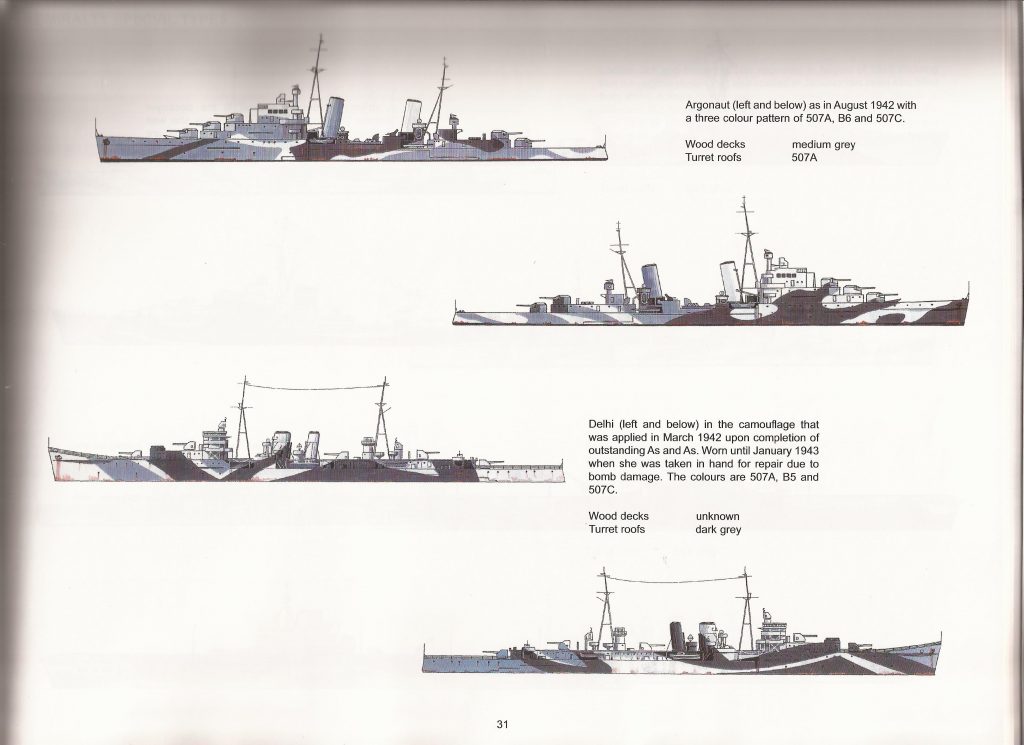

Nearly every fighting ship in the Royal Navy wore a dazzle or disruptive camouflage scheme at some time between 1940 and 1945. In 1942 the Admiralty Intermediate Disruptive Pattern came into use, and was reasonably successful in breaking up a vessel’s outline at medium and long ranges and in most weather and light conditions. The colours usually consisted of dark black grey (507A) medium grey (507B) and light grey (507C).

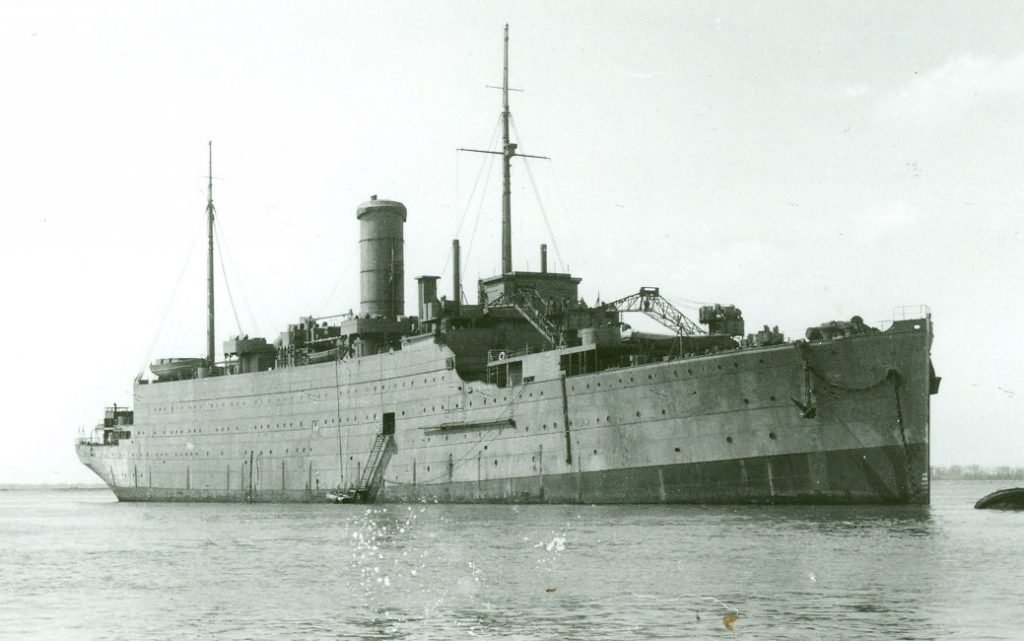

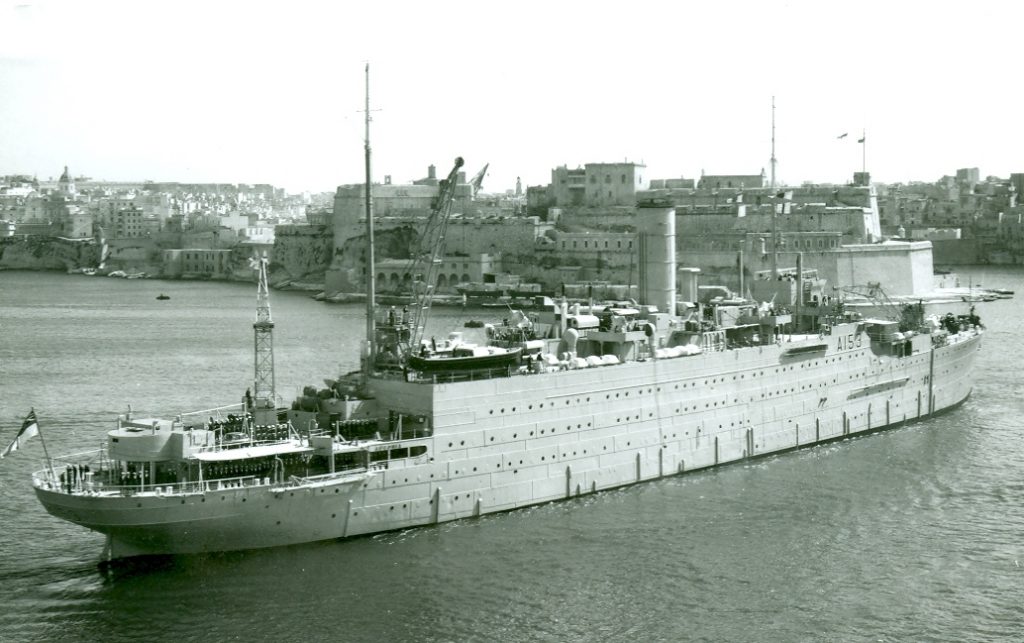

When HMS Ausonia returned to the UK in 1946, she became the flagship of the Officer Commanding the reserve fleet at Chatham. The next few years were spent in Chatham and Scotland and finally in preservation at the shipyards at Millwall, London. During this time she was painted in the Home Fleet’s overall medium grey colour.

If you can contribute in any way to this web site, a record of the Ausonia’s history, but especially with photographs and memories, please get in touch using peterjryder@gmail.com