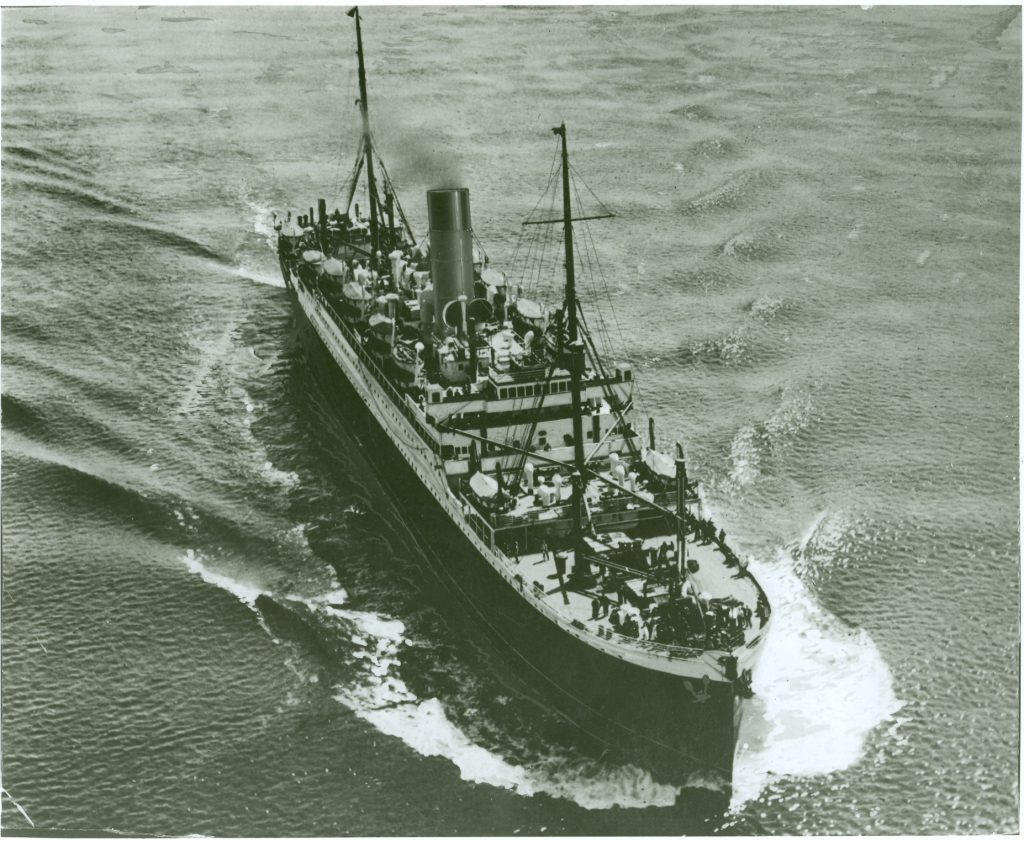

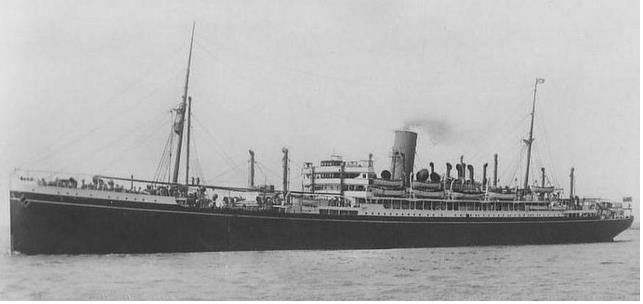

Cunard launched two batches of intermediate liners in the 1920’s, all were 13,000 tonners and intended for the London-Canada route. The first trio, the ‘A’ Class of 1922 was the Andania, Antonia and the Ausonia. The second trio, the ‘A’ Class of 1925 was the Aurania, Alaunia and the Ascania. All six ships were requisitioned by the Admiralty in 1939 and converted to Armed Merchant Cruisers mainly to protect Britain’s merchant ships crossing the Atlantic. The battle of the Atlantic was the largest naval campaign fought during the Second World War. It began when war was declared on the 3rd September 1939 and finished almost six years later.

During their commission as AMC’s they performed a sterling service with very little glory. The combination of Royal Navy and Merchant Navy worked very well, given the circumstances. The Merchant Navy might not like the Navy ‘bull’, and the Royal Navy might not have approved of the easy-going way of the Merchant Navy, but they proved that together, they made a wonderful team.

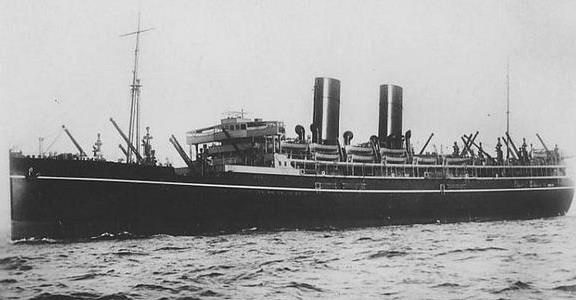

HMS Alaunia

Built by John Brown & Co in the Dalmuir Basin at Clydebank, Alaunia II was the last of the 1925 ‘A’ Class trio to be launched, taking to the water in February 1925 and making her maiden voyage from Liverpool to Quebec 5 months later on the 24th July, joining her sister ships on the Canadian service. On the 20th October 1939 she arrived back in London from Montreal and towards the end of that month she was requisitioned by the Admiralty and steamed to Gibraltar for conversion to an AMC.

She was armed with 5 ancient, 6 inch guns and 2 single 3 inch, high angle guns. She commissioned on the 27th September and after trials off Gibraltar, she returned to Berth 40 at Southampton Docks where the conversion work was completed. The dockyard painted her battleship grey and all the surplus furniture, fixtures and fittings were landed. On the 9th January 1940 an additional 3, 6 inch guns were fitted and 4 days later she left to join the 3rd Battle Squadron at Halifax Nova Scotia.

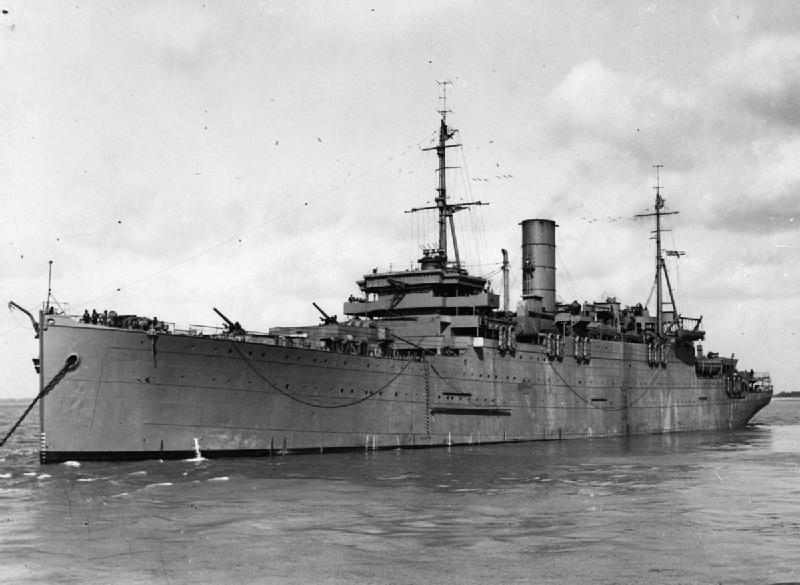

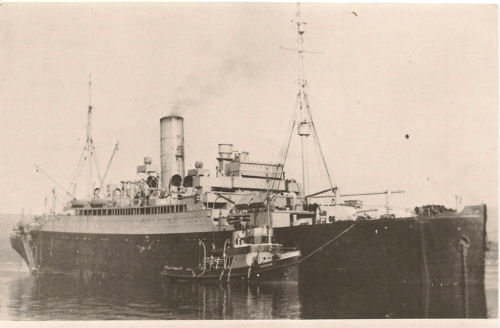

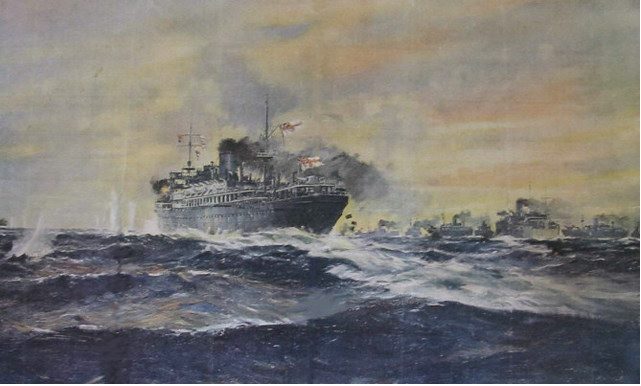

Armed Merchant Cruiser HMS Alaunia, (sister ship to Ausonia) seen here with the battleship HMS Warspite during operations round Madagascar in May 1942. In the foreground is a Grumman Martlet on the flight deck of HMS Formidable. The force had left Colombo on 24th April and put into the Seychelles on 1st May. The Fleet Air Arm carried out extensive patrols over a wide area during the operation before the covering force put into Mombasa on 10th May on conclusion of the operation.

HMS Alaunia remained on this station until mid 1941 mainly escorting convoys from Halifax to a rendezvous off Bermuda, and then in the autumn of 1941 she sailed to the Clyde and back to her builders, John Brown & Co, for a major refit. She completed her refit on the 15th December 1941 and was moved down the river to Greenock to embark stores and ammunition before sailing in convoy to Freetown, Durban and Mombasa. She returned to Durban where she remained until March 1942, when she escorted the liner Narkunda to Mombasa, their destination was originally Bombay but in the uncertainty following the disastrous battle of the Java Sea, both ships were diverted. In early April that year, when the situation had eased, Alaunia did escort a convoy to Bombay and in April 1942 she arrived in Colombo.

At this time the Japanese were on the offensive in the area and earlier in the month a Japanese naval force had destroyed 92,000 tonnes of shipping along the east coast of India and aircraft had bombed Trincomalee, sinking the aircraft carrier HMS Hermes. Admiral Somerville, who had just taken command of the Eastern Fleet, was forced, in the face of overwhelmingly superior Japanese naval strength, to retire with his fleet to Kilindini Harbour at Mombasa.

HMS Alaunia played a small part in this operation and she loaded large amounts of surplus stores and furniture for shipment to East Africa. On the 23rd April she embarked members of the Admiral’s staff and the following day sailed with the fleet, codenamed ‘Force A’, taking up station with HM warships Warspite, Indomitable, Formidable and Newcastle. After refuelling at the Seychelles on the 30th April, the fleet arrived in Kilindini on the 3rd May and Alaunia immediately disembarked the passengers and unloaded the stores.

Alaunia returned to Colombo in mid May where she was immediately quarantined after a crew member was found to have smallpox. She remained there until the middle of June when she left once again for patrols between Colombo and Kilindini. From November 1942 until January 1944 she was anchored off Bandar Abbas in Iran, with periodic refits at Bombay.

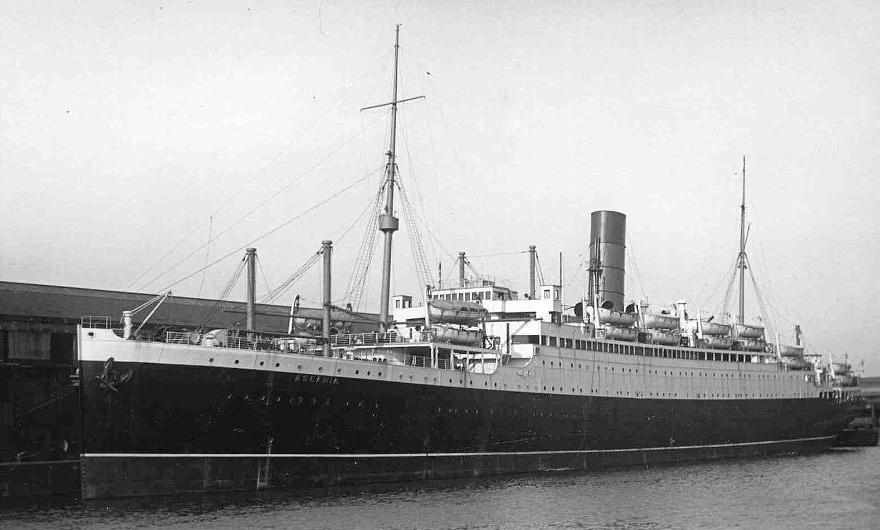

HMS Alaunia at Port Said, Egypt just before returning to England in February 1944.

After completing a refit she left for England on the 19th February 1944. Although AMC’s still had a role to play in the Indian Ocean mainly on convoy escort duties, it was decided that Alaunia should be converted into a repair ship, one reason being that she had very poor gunnery equipment, not having been modernized during her years east of Suez. She arrived in Greenock on the 2nd April and left for Devonport five days later where she was paid off on the 17th May, with most of her ships company being drafted to Portsmouth and Chatham.

After her conversion to fleet repair ship, Alaunia commissioned again on the 21st August 1945, six days after VJ Day. The urgent need for these ships had now eased and she spent the remainder of her career at Devonport, anchored to No 1 buoy or alongside No 5 wharf. She ended her days as a static training ship for engine room personnel under training at Plymouth.

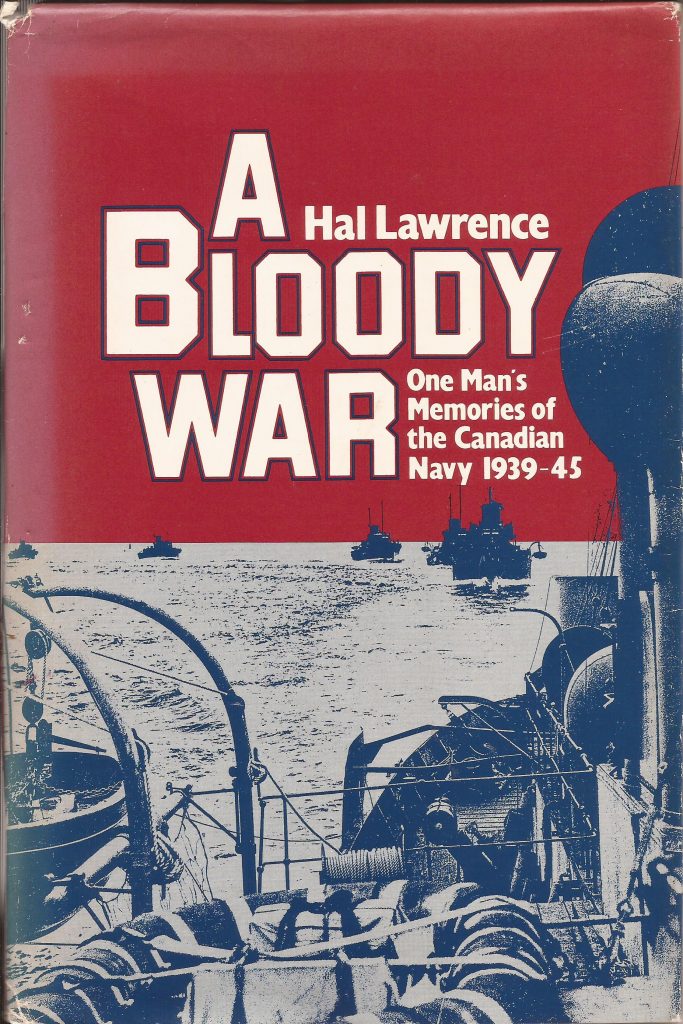

A Bloody War – One Man’s Memories of the Canadian

Printed in 1979, A Bloody War – One Man’s Memories of the Canadian Navy 1939 – 1945, is a story about the sea and about the first five and a half, of the twenty five years that Hal Lawrence, spent in the Royal Canadian Navy. This book is an engaging personal account of a young man growing up at sea. Witness to the drama of a deadly serious contest for supremacy in the Atlantic, he commemorates with genuine affection the dedicated men with whom he served. His book describes life aboard three Canadian destroyers, HMCS Moose Jaw, HMCS Oakville and HMCS Sioux, but it is his accounts aboard the Royal Navies armed merchant cruiser HMS Alaunia, from September 1939 to September 1941, which is of interest here.

In Chapter Two of his book, Hal describes the ship as she was at this time.

Alaunia had only recently been requisitioned from Cunard, but the addition of eight 6-inch and four 3-inch guns had transformed her into a warship. Nothing else was changed. The tapestries still hung in the lounges and the deep carpets received the same loving care by the same stewards who tended them in peacetime. A library of perhaps five thousand books was a solace in quiet moments and a gymnasium catered to the more energetic moods. The officers lived in the first class accommodation, the chief and petty officers in the second, and the men in the third. The peacetime crew’s accommodation was empty. Although the facilities seemed inappropriate to war, Hal soon settled gratefully into his double first class cabin with an adjoining bath.

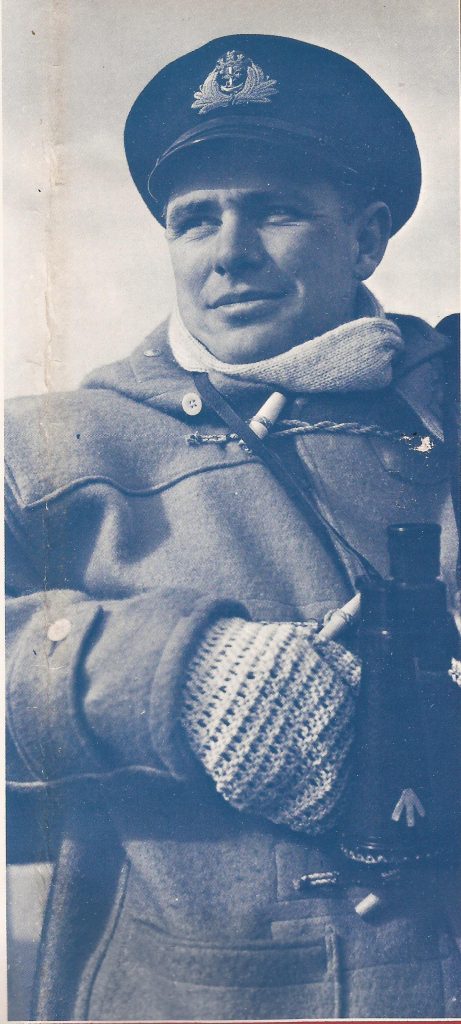

The Commanding Officer, Captain Hugh Woodward, RN, had been retired from the Royal Navy for many years and is described by Hal as a tall, heavily built man with his face brown and deeply wrinkled, his hair long and sticking out in odd places from under his cap, at sea he wore blue corduroy trousers. He would sit for hours in his chair on the bridge with only an occasional snarl about station keeping. Nobody else ever sat in “Fathers Chair”, even when he was below.

HMS Alaunia was the ocean escort for slow convoys from Halifax to the United Kingdom. After about three days out, HMCS Skeena, HMCS St Laurent and HMCS Saguenay would all return to Halifax and the Alaunia was the sole guardian of some thirty merchantmen against surface attack. Considering that her opponents in any gunnery duel would be Deutschland or Scheer, there was a certain desperation in the lookout that they kept, these German pocket battleships had a speed of thirty knots to the Alaunia’s twenty, their 11-inch guns outraged the Alaunia’s 6-inch, by ten thousand yards and the only advantage that they had, was that the holds of the Alaunia were filled with empty oil drums and ping pong balls, so that she would be hard to sink. At least that was the theory.

HMS Alaunia’s officers were mostly from Cunard White Star, the Pacific and Orient and other “posh” shipping lines. Correct, impeccable, strict and formal, many of them were master mariners and all had been RNR for years before the war. The bridge watch-keeping officers were lieutenants in their thirties, the navigator was a commander, but at this time, Hal Lawrence was a lowly Midshipman of the Watch.

Part of his duties as a Midshipman was to decode the messages sent to Alaunia from Bermuda, Halifax or Whitehall and he also spent time in the wireless room. They kept a listening watch only and never transmitted at sea, for to do so would have caused their position to be plotted by every German raider in the vicinity.

The voices Bermuda, Halifax boomed in strong, but there were also weak, short messages of ships in distress and muttered, muted conversations from around the world. Under circumstances of anoprop (anomalous propagation connected with atmospheric conditions and the Heaviside layer), they picked up transmissions from the South Atlantic, the frantic bleat of SSS, “Am being attacked by submarine”, followed by a latitude and longitude. Or the cry RRR, “Am being attacked by surface raider”, followed by the latitude but no longitude.

The German raiders would not allow the crew of the Alaunia to relax. Besides the big battleships and cruisers, there were the German armed merchant ships. Where Alaunia had a displacement tonnage of about eighteen thousand, they would be between three thousand and eight thousand and better armed with modern guns while the Alaunia’s guns were old. The dates on the breeches of the two aftermost 6-inch guns on Alaunia were 1898 and 1903. In addition, the German ships carried between two and six torpedoes, while Alaunia had none.

The gunnery engagements between the German armed merchant cruiser Thor, and Royal Navy armed merchant ships, were discussed at length in the wardrooms of Alaunia and her sister ships such as Ausonia. In July 1940, Thor had sunk HMS Alcantara with gunfire and then in November, encountered another armed merchant cruiser, HMS Carnarvon Castle, who she also sunk with gunfire.

As Hal had his action station as Officer of the Quarters of the 6-inch guns, he yearned for his guns to be the best in Alaunia, however as the crew of Alaunia were mostly Royal Fleet Reserve sailors, most of his gun crew were over twice his age and just didn’t take him seriously.

When the Scheer broke out through the Denmark Strait in November 1941 and started attacking one of the Halifax-UK convoys, the armed merchant cruiser HMS Jarvis Bay scattered her convoy and engaged the German ship. The Jarvis Bay’s 6-inch guns were no match for the Germans 11-inch and she was soon ablaze but her heroic fight had given the convoy twenty two minutes in which to escape. The Scheer went on to sink five of the thirty seven merchant ships in the convoy and HMS Alaunia was ordered to straddle one of the Scheer’s anticipated escape routes.

With thumping hearts and dry mouths they were scrambled to their action stations whenever a mast showed over the horizon. Hal’s gun crew were transformed, alert, eager, snappy and looking to their officer to direct their fire when the Gunnery Officers central control was wrecked. With intense relief, the “enemy” masts all turned out to be independently routed merchantman and Alaunia never saw the Scheer, or the German battleship Hipper, which also broke out through the Denmark Strait and sailed across the Alaunia’s Halifax – UK convoy route.

For months, HMS Alaunia plodded its way across the bleak Atlantic at eight knots, sometimes reduced to four knots by gales and stragglers. Hal always hoped for stragglers, because the Captain would curse and swing Alaunia out of her station between the centre columns of the convoy and thrash back at a glorious eighteen knots, cutting log-lines with lordly indifference.

Within four hundred miles of England they were met by Royal Navy destroyers and two more days steaming put the convoy safe in harbour. For Alaunia, once the rendezvous was made, she would swing about and head west to Halifax.

In September 1941, Hal Lawrence left Alaunia and exchanged his luxury accommodation for the cramped quarters of a rolling corvette. Awarded the Distinguished Service Cross for his part in the sinking of a German U-Boat, he finally retired from the Canadian Navy as Senior Officer in Command of the Eleventh Escort Squadron in 1965.

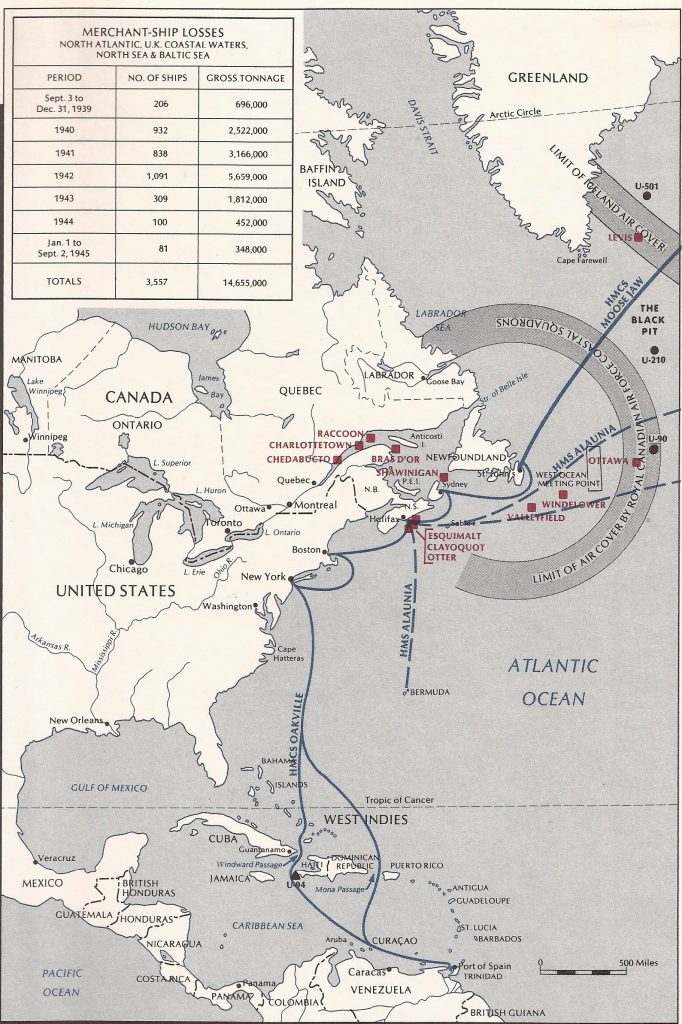

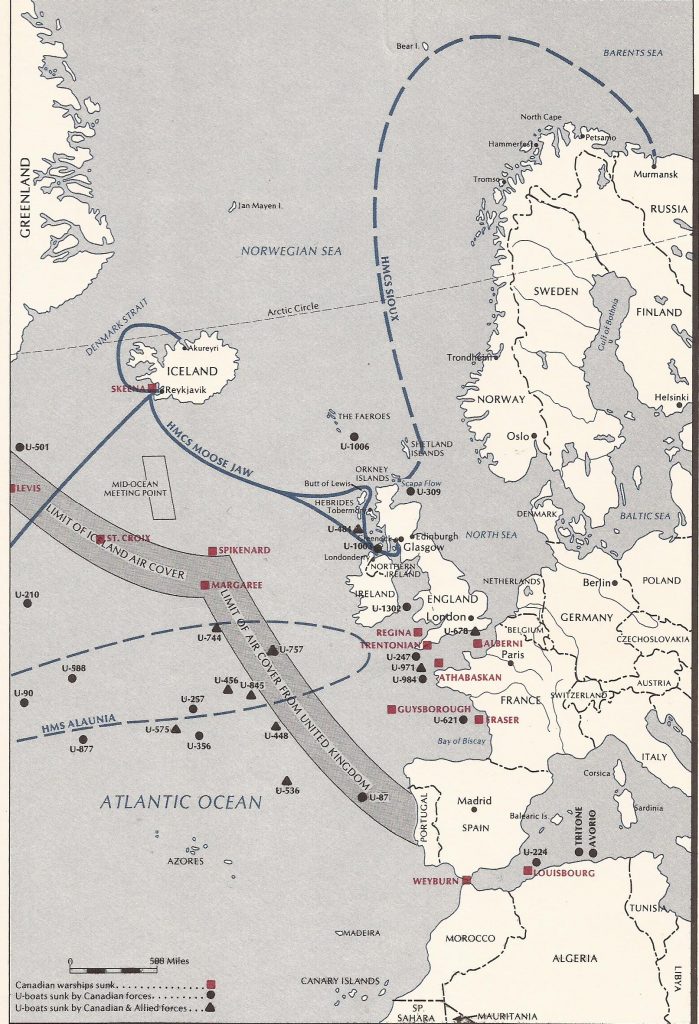

Two maps showing the regular routes of HMS Alaunia and the three Canadian destroyers, HMCS Moose Jaw, HMCS Oakville and HMCS Sioux, which Hal Lawrence serve on 1939 – 1945.

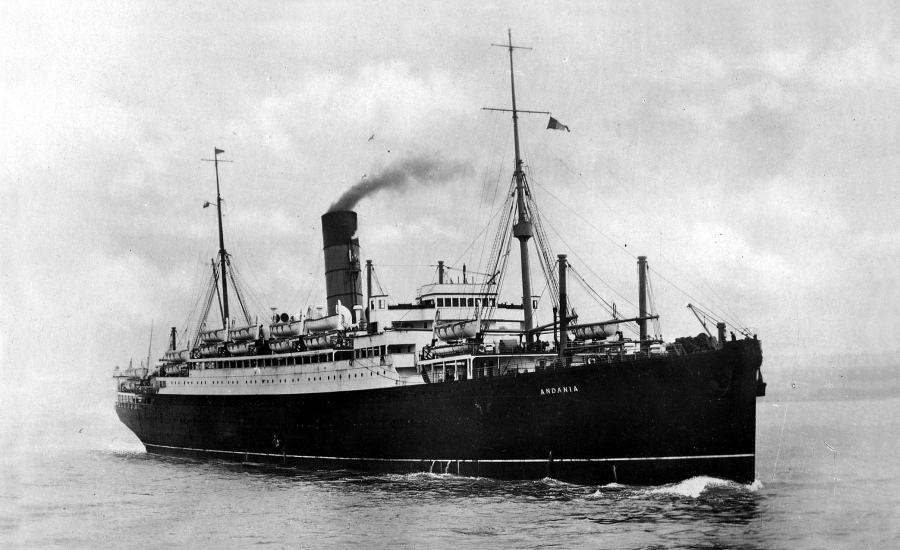

HMS Andania

Built by Hawthorn, Leslie & Co at Hebburn-on-Tyne, Andania II was the first of the 1922 ‘A’ Class trio to be launched, making her maiden voyage from London to Montreal on the 1st June 1922. In August 1939 the Andania was on the Liverpool, Belfast and New York route and when she arrived back in England in September 1939 she was requisitioned by the Admiralty and steamed to the Cammel Laird’s yard at Birkenhead for conversion to an AMC.

Built by Hawthorn, Leslie & Co at Hebburn-on-Tyne, Andania II was the first of the 1922 ‘A’ Class trio to be launched, making her maiden voyage from London to Montreal on the 1st June 1922. In August 1939 the Andania was on the Liverpool, Belfast and New York route and when she arrived back in England in September 1939 she was requisitioned by the Admiralty and steamed to the Cammel Laird’s yard at Birkenhead for conversion to an AMC.

She commissioned under Captain D Bain RN on the 9th November 1939, the same day that most of her ship’s company arrived in a draft from Devonport. She was armed like most AMC’s in the early weeks of the war, with eight elderly 6 inch guns and two anti-aircraft guns. On the 12th November she left her berth and moved into the Alfred Dock for the final stages of her conversion. Four days later she left the Mersey and after nine days of trials in Liverpool Bay she left for Greenock to join the Northern Patrol.

A drawing of the Armed Merchant Cruiser HMS Andania in 1940

On 15th June 1940, she was on patrol in a position 62° 36’N/15° 9’W, (230 miles west-northwest of the Faroe Islands) steering a course of 240° at 15 knots. It was 11.30 pm and Captain Bain had just arrived on the bridge, when a heavy explosion shook the ship as a torpedo hit her on the starboard side aft, between five and six holds. The alarm was sounded, the crew closed up to their stations and the starboard guns opened fire on a periscope that had been spotted about 1,500 yards away. Andania settled by the stern, with a list to starboard and lost headway, but this was rectified by the engineers transferring fuel oil. Her rudder was out of action and the main generators in the engine room were flooded and of no use. At 11.45 pm a second torpedo was sighted approaching from starboard, but this passed harmlessly 100 yards astern. Half an hour later at 12.15 am, a third torpedo passed 50 feet astern and at 12.50 am a fourth torpedo also missed the ship, passing astern. The track of this torpedo was clearly visible and the gunners continued to fire on the suspected position of the submarine but could not locate her in the darkness, but their firing did have some effect as no more torpedoes were fired.

When the damage had been assessed it was found that five, six and seven holds were flooded and despite all pumps being in operation, the water level elsewhere was rising, particularly in the engine room. At 1.15 am Captain Bain ordered all personnel who were not required, to abandon ship and to stand off close by. At 2.30 am, with the water gaining rapidly, the engine room too was abandoned. By 2.40 am the ship was down 15 degrees by the stern and Captain Bain gave the order to abandon ship.

The crew were all picked up by the Skallagrinur, an Icelandic trawler, with no loss and only two men injured. At 6.55 am HMS Andania was standing vertical in the water and within a minute she sank by the stern. The trawler continued on its course to Hull, but the Andania’s crew were transferred to HMS Forester about 36 hours after their rescue and landed them at Scapa Flow on the 17th June.

The sinking of HMS Andania was claimed by the German U-boat, UA, which had first spotted her in heavy rain at 15.24 on the 13th June. The U-boat had followed the ship but had lost her several times due to bad visibility, darkness and the fast zigzagging patrol course that she had been sailing. UA had fired a spread of three torpedoes at the Andania, on the 14th June at 12.17 pm but these had all missed and after the attack she lost sight of the Andania, (these torpedoes were apparently not observed aboard Andania). It was another 24 hours before the ship was sighted again and was successfully hit. UA did in fact fire another torpedo after 8 minutes of the initial attack, but this turned out to be a dud. Captain Hans Cohausz of the UA finally gave up his attack on the Andania after two attempts of coups de grace had missed due to the high seas.

Five days later, the Admiralty announced the loss of the Andania to the press.

The U-A in harbour with Hans Cohausz on the bridge

The last known photograph taken of HMS Andania showing Robert Woods on her bridge just prior to her loss in June 1940.

HMS Antonia

Built by Armstrong Whitworth at Barrow-in-Furness, Antonia was the second of the 1922 ‘A’ Class trio to be launched, making her maiden voyage from London to Montreal on the 15th June 1922. In August 1939, at the outbreak of World War II the ship was on its way to Montreal. On her return to Liverpool the Antonia was chartered for service as a troop ship and for the first 12 months of the war she brought Canadian troops to England and carried Government passengers and child evacuees west bound to Canada and the USA.

In October 1940 she was finally requisitioned by the Admiralty. Although it was first intended that she should become an armed merchant cruiser the need for a repair vessel took priority. As a result the Antonia spent 10 months in Portsmouth being converted into a fleet repair ship and was then bought from Cunard by the Admiralty. On 19 August 1942 it was commissioned into the Royal Navy and renamed HMS Wayland.

HMS Ascania

Built by Vickers Armstrong on the Tyne, Ascania was the first of the 1925 ‘A’ Class trio to be launched, making her maiden voyage from Southampton to Montreal on the 22nd May 1925. In August 1939, she was requisitioned by the Admiralty and converted to an AMC, after commissioning on the 16th October 1939 she joined the 3rd Battle Squadron at Halifax Nova Scotia.

She was employed in this role until October 1941, when she left the Clyde with a convoy bound for the Middle East via Freetown, Durban and Port Elizabeth, where she was detached from the convoy and ordered to Colombo. From there she was ordered south through the dangerous waters of the Indian ocean via Freemantle and Melbourne to Auckland in New Zealand. She remained on this station for some months patrolling the Pacific waters to Suva with HMNZS Monowai. This was a very active theatre of war at that time, with the Japanese advancing southwards.

In August 1942, Ascania left New Zealand for England, sailing via Panama up the east coast of the USA and across the Atlantic in convoy to Southampton where she paid off and underwent conversion to a landing ship (infantry). The purpose of these ships was to carry the bulk of an invasion force to a beachhead where they would be transferred to assault landing craft for the final run into the beaches. During her service in this role the Ascania took part in the invasion of Sicily, Salerno and in 1944 the Anzio landings.

HMS Aurania

Built by Swan Hunter & Wigham Richardson on the Tyne and on the same slipway as the Mauretania, Aurania was the second of the 1925 ‘A’ Class trio to be launched, making her maiden voyage from Liverpool to New York on the 13th September 1924. In August 1939, she arrived on the Thames and was immediately requisitioned by the Admiralty. The Aurania was converted into an armed merchant cruiser and commissioned into the Royal Navy on 15th October 1939. For nine months she served as an escort ship on the Northern Patrol and then in April 1940, after a refit, she joined the Halifax Escort Force.

At 10.50 am on the 12th July 1941 HMS Aurania left her anchorage off Sydney, Cape Breton, as escort for a Reykjavik bound convoy. By 8 pm the next evening there were icebergs in sight and the following morning she took up station ahead of the convoy. By 3.30 pm she was passing through a field of loose ice and thick fog banks, and an hour later she was passing large icebergs as close as six cables to her. At 7.30 pm the fore castle lookout was doubled and 16 minutes later, as Aurania emerged from a fogbank, a large iceberg loomed up ahead. Despite putting the engines full astern and the wheel hard to port, at 7.20 pm she hit the iceberg bows on.

She was in a position of 51° 49’N/55° 50’W, off the coast of Labrador and she immediately signalled the convoy to stop. The whole convoy remained stationary until midnight before moving ahead cautiously once again. At daybreak on the 15th July the remainder of the convoy continued on its original course whilst the Aurania made her way slowly to Halifax, where she anchored on the evening of the 17th July. The next day she went along side berth 39 and after disembarking the RAF personnel onboard and discharging her cargo of fruit, she left Halifax for Newport News in the United States for repairs.

HMS Aurania completed her repairs on the 12th September 1941 and two days later, after taking on ammunition in the Hamplin Roads, she left the USA for Halifax, via Bermuda. She arrived back in the Canadian port on the 26th September and 17 days later, on Monday the 13th October, she sailed from Halifax for the Clyde, steaming in a convoy of HM ships which included the AMC’s Wolfe, Ranpura and Maloja. By 2.27 am on Tuesday the 21st October and convoy was in a position 50° 48’N/18° 41’W when a torpedo hit HMS Aurania on the port side forward. The ship took a 25 degree list to port so her captain turned to starboard in an attempt to get away from the submarine, the listing decreased and speed was increased to 12 knots.

However, from somewhere in the ship the order ‘abandon ship’ was circulating when in fact the captain had only ordered ‘turn out the boats’. Lifeboat P2 was lowered with five occupants and was severely damaged when it hit the water as the ship was still under way and had to be cut adrift. Although thrown into the sea by the impact, four men were picked up by HMS Croome, which had been detached to search for survivors. Another crew member from Aurania was also lost at this time when he fell overboard while preparing the ships cutter for use in case it should be needed. It was not known who had ordered the ship to be abandoned, but it could have been disastrous as the engine and boiler rooms were left unattended. Fortunately the engineering officer of the watch realised that the captain intended to go on steaming and he remained below until he was rejoined by the others.

Although HMS Aurania had been badly damaged on the port side between Nos 2 and 3 holds, she was not on fire and the lighting system and pumps were working, so there was every chance of getting the ship back to the Clyde. Once daylight came, Hudson aircraft of Coastal Command kept a continuous reconnaissance overhead and at 3.45 pm on the 23rd October, HMS Aurania anchored in Kames Bay off the island of Bute.

A month later, after salvage teams had cleared her holds, the Aurania was moved into a floating dock at Rothesay Bay for repairs. She remained there until the 12th February 1942 when she was refloated and anchored off Greenock. By this time there was an urgent need for heavy repair ships and the Admiralty purchased the Aurania from Cunard and moved it to Devonport to be converted for this role. She arrived alongside No 5 berth at Devonport dock yard on the 6th March, her days as an AMC over. When she emerged she had a new role and a new name, HMS Artifex.

The attack on HMS Aurania on the 21st October was claimed by the German U-boat, U-123, which had fired a spread of three torpedoes at the group of five AMC’s which had been trailing the SL89 convoy. The U-boat report differs to the Aurania’s action report in that it claims that two torpedoes hit the Aurania, one forward on the bow and a second underneath the bridge. Following the attack, U-123 was pursued by the convoy escorts and retreated from the area, but the following morning at 10.09 am it came across the Aurania’s sinking lifeboat and rescued Leading Seaman Bertie Shaw, taking him back to Germany as a POW.

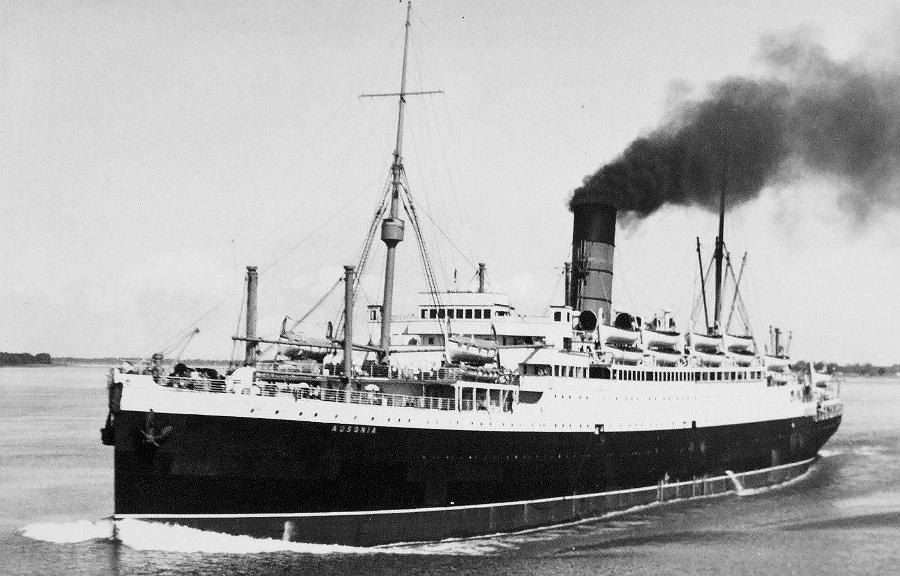

HMS Ausonia

Built by Armstrong Whitworth at Newcastle upon Tyne, Ausonia was the last of the 1922 ‘A’ Class trio to be launched, making her maiden voyage from Liverpool to Montreal on the 31st August 1922. In August 1939, Ausonia was requisitioned by the Admiralty and went up the Tyne where she was converted to an AMC. The work was completed on the 7th November when her ship’s company joined her at Chatham and the following day, at 9 am, she commissioned into the Royal Navy under Captain D. Wizey RN.

After carrying out trials off the mouth of the Tyne, she sailed for Portsmouth at 3.45 pm on 13th November 1939 passing through the dangerous waters off The Downs at just before midnight. After spending 8 days in the Solent, she fuelled at Portland on the 24th November and the following day, in storm winds, she sailed for Halifax to commence its role as an escort for Atlantic convoys.

The crew of the newly commissioned HMS Ausonia was a mixed lot, living on the starboard side were the Royal Navy seamen, reservists stiffened by a few regulars and naval pensioners and on the port side were the Merchant Navy, engineers, firemen, greasers, cooks and stewards. Normal duties meant 4 hours on and 8 hours off. 4pm – 6pm (1st Dog Watch) and 6pm – 8pm (2nd Dog Watch) meant that no one worked the same hours on succeeding days. Call outs at any time meant “action stations” with all guns manned.

There were also depth charges that could be released over the stern should a U-boat be sighted, but unlike other warships, they had no equipment to detect them. This was a weapon more suitable for destroyers with the speed to escape the impact area of the charge. The ships had Paravanes, which could be used in shallow waters to cut the mooring wires of sunken mines. Internal communication for the ship was by tannoy broadcast or to the gun positions by headset via the crew communication number. Gunnery drills were practised day and night for the main armament of 6” guns and a good crew might manage to reach 30 rounds per minute on their gun.

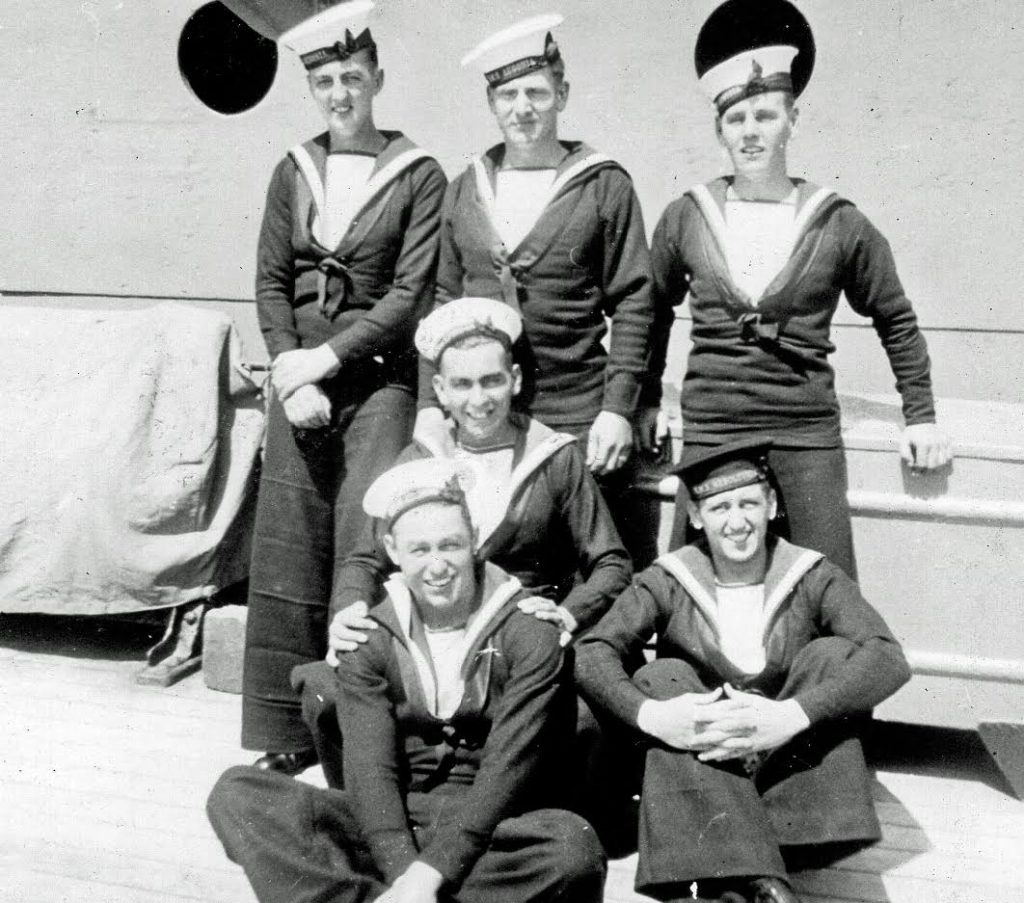

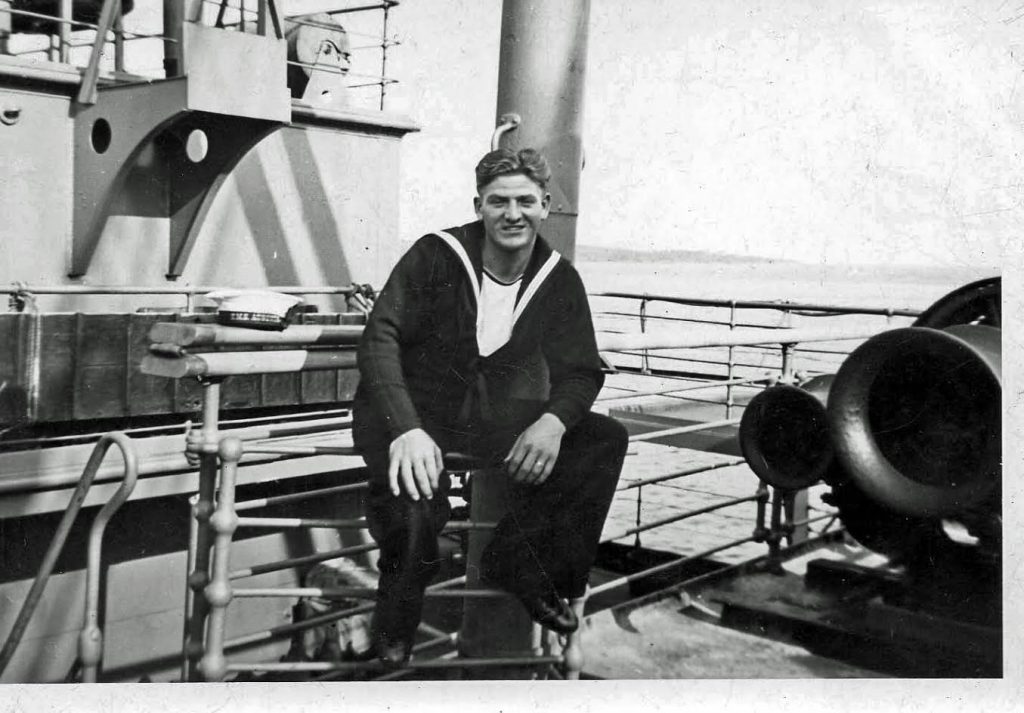

Starboard Forecastle, S1, 6” Gun Crew on board HMS Ausonia 1940.

HMS Ausonia forecastle with a Paravane in the background.

Over the next two years she escorted numerous convoys from the Canadian east coast to a position south of Iceland. The ship would then refuel at Hvalfjord and return to Canada with the westbound convoy. Very often on these runs she would carry RAF personnel to and from the training stations in Canada. By late 1940, Captain G. Freyberg CBE RN (the brother of the New Zealand Major General Bernard Freyberg VC) had taken command.

In November 1940, when the HMS Jervis Bay was sunk whilst protecting an Atlantic convoy, HMS Ausonia was in the same area escorting another convoy. Fortunately, neither she nor the convoy that she was escorting were located by the German battleship Admiral Scheer.

In March 1941 she made a patrol in the Denmark Strait before sailing to Harland & Wolff’s dockyards, in Belfast, for a refit. Whilst in Belfast both the city and shipyards were bombed by German aircraft, so the Ausonia was moved and the refit completed, in Cardiff, between the 8th November 1941 and the 15th January 1942. Once complete, she returned to Halifax.

In the middle of February 1942, she sailed south to Bermuda where she carried out patrols in the Sargasso Sea but now, with the increasing need for repair and depot ships, the Ausonia’s role was about to change. The first two AMC’s to be earmarked for this role were the Ausonia and the Aurania. In March 1942 approval was given to convert the Ausonia into a repair ship and she left Bermuda on the 24th March for Portsmouth, arriving there on the 6th April at 6.24 pm. On the 20th April dockyard contractors started work on discharging the buoyant ballast and she paid off as an AMC on the 3rd May 1942.

HMS Ausonia Seaman’s Messdeck.

Cleaning the Port Forecastle, P1, 6” Gun on board HMS Ausonia 1940.

HMS Ausonia lower bridge, sports event near the equator, South Atlantic.

HMS Ausonia – Ships sports, promenade deck, Port side.

September 1939 – March 1942

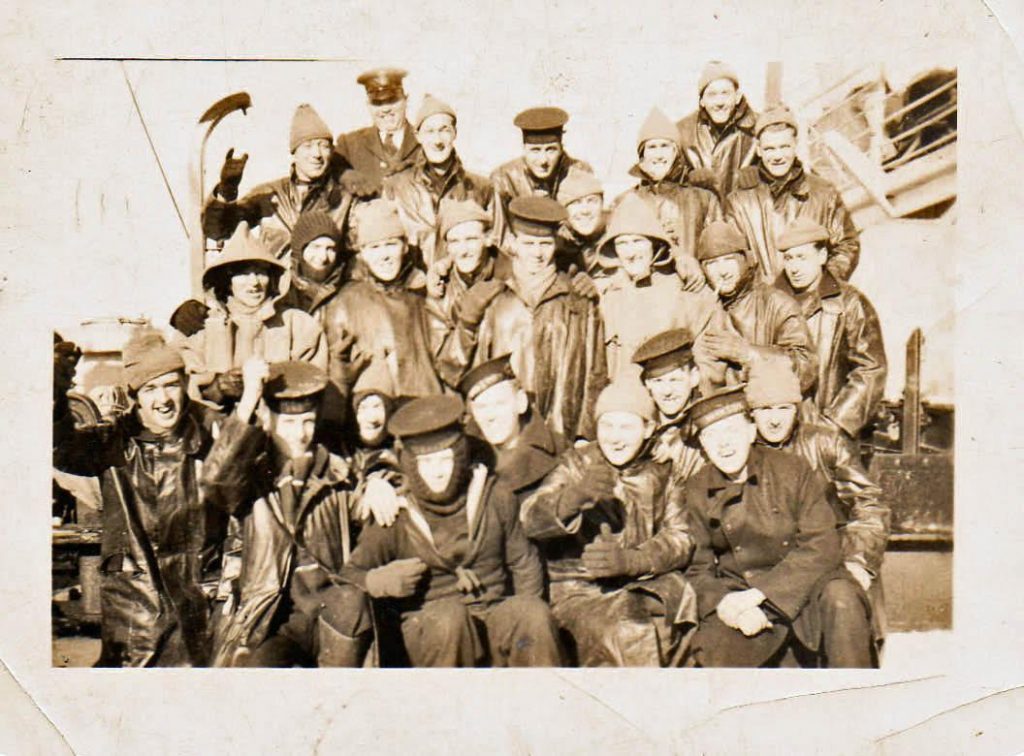

The following five photographs were all taken on the forecastle of HMS Ausonia between September 1939 and March 1942.

HMS Ausonia 1939 – 1942 Armed Merchant Cruiser

Battle Honours – Atlantic 1939 – 1941

November 1939 to May 1940 – Halifax Escort Force

June 1940 to April 1941 – Bermuda and Halifax Escort Force

May 1941 to October 1941 – North Atlantic Escort Force

Code letters: KMQV Official Number: 145970

Transcribed from the Lloyd’s Register of British and Foreign Shipping 1939

Rigging:

Steel twin screws steamer; 2 steel decks & Shelter Deck sheathed in wood; 3rd deck in holds except No. 4 & 5; 10 partly cemented bulkheads; fitted with electric light, refrigerating machinery, wireless, direction finder & submarine signalling device; cellular double bottom 442 feet, 1,810 tons; Deep Tank forward 1,456 tons; tanks in way of tunnels 45 feet, 382 tons; Forward Peak Tank 106 tons; Aft Peak Tank 57 tons

Tonnage:

13,912 tons gross, 10,696 under deck and 8,527 net

Dimensions:

520 feet long, 65.3 foot beam and holds 39.1 feet deep;

Bridge Deck & Forecastle 425 feet; Promenade Deck 243 feet

Construction:

1921, Armstrong Whitworth & Co. Ltd. in Newcastle

Propulsion:

4 steam turbines double reduction geared to 2 screw shafts; operating at 220 p.s.i.; 1,640 nominal horsepower; 2 double ended & 2 single ended boilers; 24 corrugated furnaces; heating surface 19,440 sq. ft (by the builders)

Speed:

15 Knots

Owners:

Cunard Steam Ship Co. Ltd.

Port of registry:

Liverpool

Armament:

8 x 6 inch guns

2 x 3 inch guns

2 x .303 Lewis machine guns

Anti Submarine Weapons:

2 Depth Charge rails – 8 Depth Charges

“H.M. Armed Merchant Cruiser Ascania”

The following is an article written by Guy Stafford in which he tells the story of a Cunard liner that went to war as an armed merchant cruiser in 1939. HMS Ascania, flying the White Ensign played an important, if unspectacular, part in the early years of the war at sea.

It was 8.am on a Saturday morning in late September 1939. The war was in its third week and the twenty naval ratings waiting outside the drafting office at HMS Excellent on Whale Island were wondering what the future had in store for them. Each had received a draft chit for AMC (Armed Merchant Cruiser) C5. They knew they were due to join her that day, but as to the name of the ship and where she was berthed, they had yet to learn.

Thirteen and a half weary hours later they arrived at a blacked-out Woodside Station at Birkenhead. There was a lorry to meet them and after a short trip through the darkened streets it entered Cammell Laird’s yard and pulled up alongside a steamer in the dry dock.

That she was a Cunarder was obvious from her colours, but it was not until after the white-coated stewards had shown them to their accommodation that they knew her as the Ascania. The chief and petty officers were accommodated on ‘B’ deck, the remainder on ‘C’ deck; cabins being an unheard-of luxury to the naval men.

Three hectic weeks followed. Eight six-inch guns arrived on the quayside to be hoisted on board and bolted down to the gun supports built in when the Ascania was constructed; four to port and four to starboard. A small director and range finder were fitted to the upper bridge, and a height finder on a specially constructed platform abaft the single funnel. Two three-inch high-angle guns and twin Lewis guns on the wings of the bridge formed the anti-aircraft armament.

The magazines were constructed in the holds fore and aft. Small davits with electric winches served as shell and cordite hoists to each magazine. A coat of battleship grey was applied and the once-proud Ascania had become a warship.

During the busy three weeks at Cammell Lairds, a relationship had sprung up between the small naval party and those members of the merchant navy crew who were to remain with the ship on T124 Articles of Agreement. The initial prejudices quickly gave way to curiosity and interest in each other’s’ jobs. Many lasting friendships were formed in those early days.

At the end of the three weeks, the main body of the naval crew arrived. It was a motley collection comprising of recalled pensioners, RNR, and RNVR ratings. The only active service ratings were the chief gunner’s mate and the young ordnance artificer joining his first ship.

With the ship’s company complete and under the command of Captain C.H. Ringrose-Wharton, RN, HMS Ascania went to sea for the first time – just for the day. Two days later, stored and fully armoured, she sailed for an unknown destination. Rumour was rife, with the best bet being Scapa Flow for duties on the Northern Patrol but once clear of Anglesey, the Ascania turned on a southerly course and eventually steamed into Spithead. After some hours the ship entered Portsmouth Harbour and an unexpected weekend leave was granted to some of the crew. On Monday morning she sailed for Portland.

During the week that followed, most days were spent at sea on gun trials. The six-inch Mk VII guns dated from between 1898 and 1904 and some problems were experienced with these elderly pieces and a great deal of glass was shattered during the firing, particularly on the promenade deck. The three-inch guns were 1917 vintage and cause no problems other than the lack of training for the crews.

On the Thursday evening of the Ascania’s week at Portland, two members of the ship’s company were in a pub discussing the possibility of weekend leave again, only to be told by the barmaid that: “if you’re off that liner, you’ll be on your way to Canada with a load of bullion come Saturday!” The men laughed, but, strangely enough, a small coaster came alongside and some strange-looking boxes were loaded under armed guard and stowed down below.

Saturday morning dawned bleak, grey and very wet. HMS Ascania left harbour with a two destroyer escort, and for several hours steamed up Channel until well out of sight of land, then she turned, left her escort, and headed out into the Atlantic.

The passage was rough and the weather still very wet when six days later Chebucto Head loomed out of the mist and the Ascania steamed into Halifax harbour and berthed at Pier 22. The first ship of the 3rd Battle Squadron had arrived! Later she was joined by her sister Cunarders Alaunia and Ausonia, and later still by the Jervis Bay, Montclare and other Armed Merchant Cruisers.

After a few days in port the Ascania sailed as escort for one of the first convoys to leave Halifax. The weather was calm but foggy, and with the ships unused to sailing in company, the inevitable happened. The Oropesa and the Manchester Regiment collided, and the latter was reported sunk. This was the first of many such convoys, some fast but most desperately slow.

In January 1940 the pattern was altered. Up to then all the convoys had been handed over to the Local Escort Force off the coast of Ireland, but on this occasion the Ascania went all the way, right up the Clyde to refit in Glasgow. This gave the ship’s company seven days’ leave for each watch. It was during this period that the ship was fitted with depth charge throwers, but unfortunately no asdic, so the depth charges were of doubtful value – they were certainly never used in anger. An early type of radar was fitted with the enclosed aerial mounted on a small tower forward of the funnel.

With the refit completed, the Ascania went back on station to Halifax, on the way forming part of a chain of ships covering the first ‘secret’ voyage of the Queen Elizabeth to New York. There were changes in the routine for the AMCs, with convoys to Bermuda and the West Indies, where at least the weather was more kindly.

There was a not-so-welcome change in the routine for the Atlantic convoys. Where previously the handover to the local escort had meant a swift trip back to Halifax, the new idea was for the AMCs to put into Reykjavik to refuel, and then to carry out a twelve-day patrol of the Denmark Strait.

It was during this period that the Ascania was to demonstrate that she bore a charmed life. She had just returned to Halifax from a convoy and had secured alongside Pier 36, ahead of the Jervis Bay, when word went round that the stay in port was going to be very brief. The Ascania was quickly stored and fuelled to sail with another convoy the following morning. The Jervis Bay remained alongside with engine trouble. The convoy was an ‘over and back’ job so it was not so bad after all. The local escort appeared right on time and the Ascania headed back to Halifax.

The Aberdeen & Commonwealth Line steamer Jervis Bay

The Officers of the Jervis Bay photographed in 1940 for the ‘Telegraph-Journal’, a local newspaper in St John, New Brunswick.

On the evening of 5th November 1940, hands went to ‘night action stations’ as usual, checked all the equipment, and then reverted to ‘cruising stations’. Half-an-hour later it was ‘action stations’ again and it was obvious that the Ascania had increased speed and was turning back. The word was quickly passed to all positions that the Jervis Bay was in action with a German pocket battleship and the Ascania was going to her assistance.

The German pocket battleship Admiral Scheer

The ship’s company prepared for the worst. The Ascania’s six-inch guns were no match for the eleven-inch guns of the Admiral Scheer. Two hours later the Ascania was ordered to resume her passage to Halifax, and it was with very mixed feelings that this order was obeyed.

A painting of the Jervis Bayshown here engaging the German pocket battleship Admiral Scheerand thus giving Convoy HX72 two hours to disperse. Painted by Frank H Mason, it was especially commissioned for the March 1941 edition of The Navy magazine.

Meanwhile across the Western Ocean the drama was being played out. Against hopeless odds Captain Fogarty Fegen of the Jervis Bay turned his ship towards the enemy, her ancient guns blazing defiantly. For two hours the Jervis Bay fought on, giving valuable time for the convoy to scatter before she succumbed to her mighty opponent.

Much has been said about the ineffectualness of armed merchant cruisers, particularly by those who saved in them. Too big, too slow, poorly armed, all of which was true; but in those two short hours the Jervis Bay justified the existence of them all.

The crew of the Ascania learnt the full story of the Jervis Bay when they arrived back in Halifax and the unanimous feeling was that they should have gone on to assist their squadron mates. But orders, given by someone in a position to know the whole picture, are made to be obeyed, and so the Ascania survived to carry on her work

The month of April 1941 found the Ascania patrolling wearily in the Denmark Strait. On the twenty-second of the month her twelve days were up and she handed over the area to HMS Rajputana. As the Ascania steamed into Reykjavik a signal was received to say that the Rajputana had been sunk after being torpedoed by the Scharnhorst.

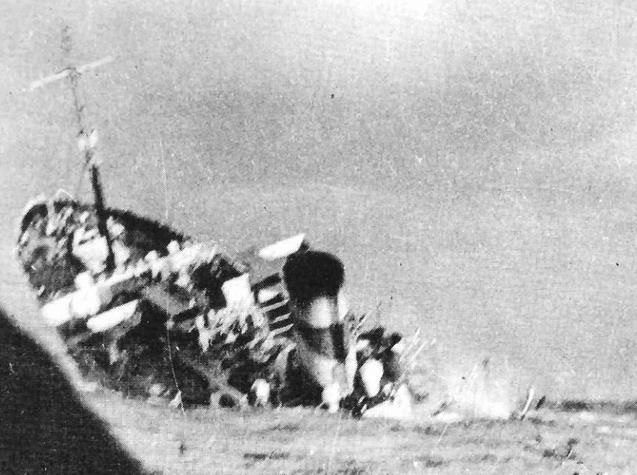

The Peninsular & Oriental Steam Navigation Company’s Rajputana

The end of the Rajputana in the Denmark Strait

A month later the Ascania was back patrolling the Strait. The weather had, for several days, been sparklingly clear with the mountains of Iceland and Greenland standing out on the horizon. On the twelfth day, down came the fog. That afternoon, as the Ascania clawed her way through the murk, there was a sudden alarm – ‘Hands to action stations’.

A dark shape loomed out of the fog. An aldis lamp flashed – it was HMS Norfolk shadowing the enemy. The Ascania was to remain on station while the scene was set for the coming battle. She might be needed, perhaps in a shadowing role if the enemy doubled-back, or perhaps even to sacrifice herself while the capital ships came up.

The following morning the Ascania’s captain broke the news to his ship’s company: the mighty Hood had blown up, the Prince of Wales was damaged and the Bismarck was on the loose somewhere in the Atlantic. It was a frightening prospect. The Ascania remained on patrol until the BISMARCK was found and destroyed.

In September 1941 the Ascania returned to the Clyde, and a few days later was despatched to Southampton for ‘tropicalisation’. This involved stripping out the cabins on ‘C’ deck and the construction of proper mess decks. An addition was made to the armament with two rocket projectors situated abaft the bridge. These were considered more dangerous to the ship than to the enemy!

Leaving Southampton for the Clyde, the Ascania joined a large convoy heading south for Freetown. From there she sailed alone to Cape Town and Port Elizabeth. In the aftermath of the fall of Singapore she sailed for Melbourne and a week later left for Auckland to be attached to the Royal New Zealand Navy. She made many trips as a troopship until June 1942 when she sailed for the UK.

The Ascania passed through the Panama Canal and joined a convoy bound for Key West. This suffered numerous U-boat attacks, but because of the Ascania’s lack of asdic equipment, her depth charges were not used. From Key West, the Ascania sailed north to New York, and a week later proceeded to Halifax to join an eastbound convoy to the Clyde.

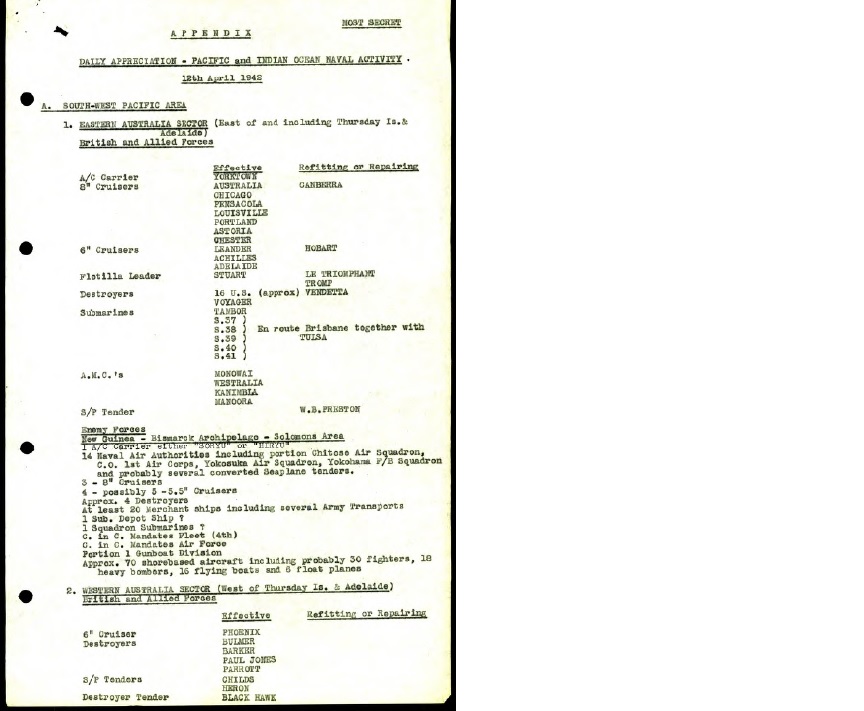

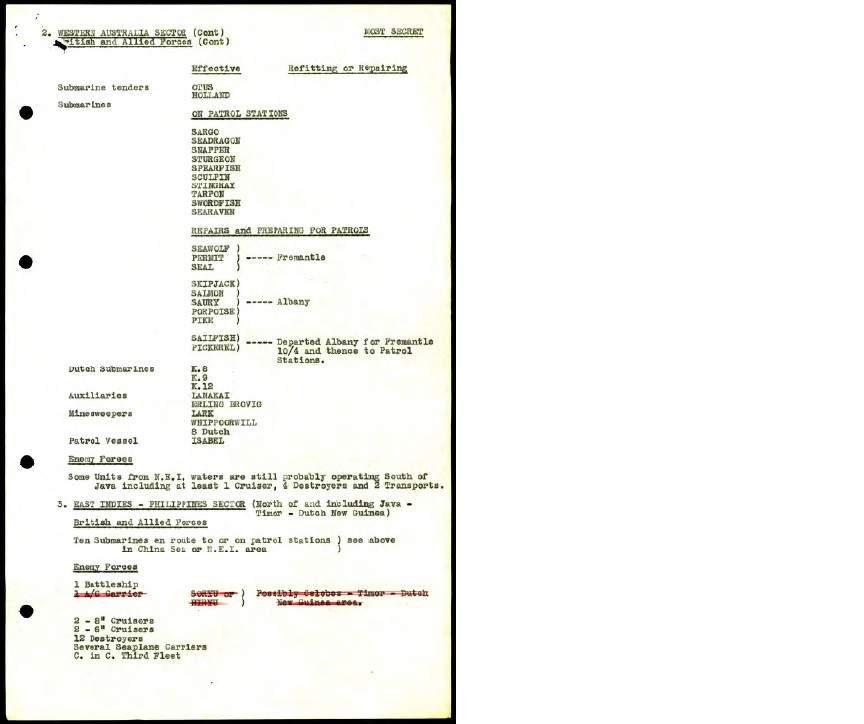

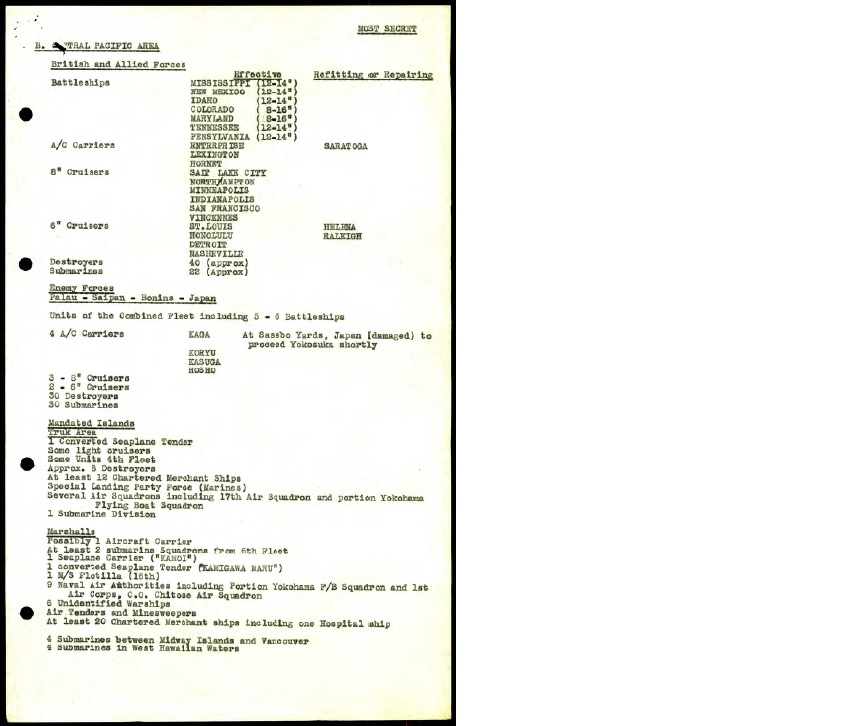

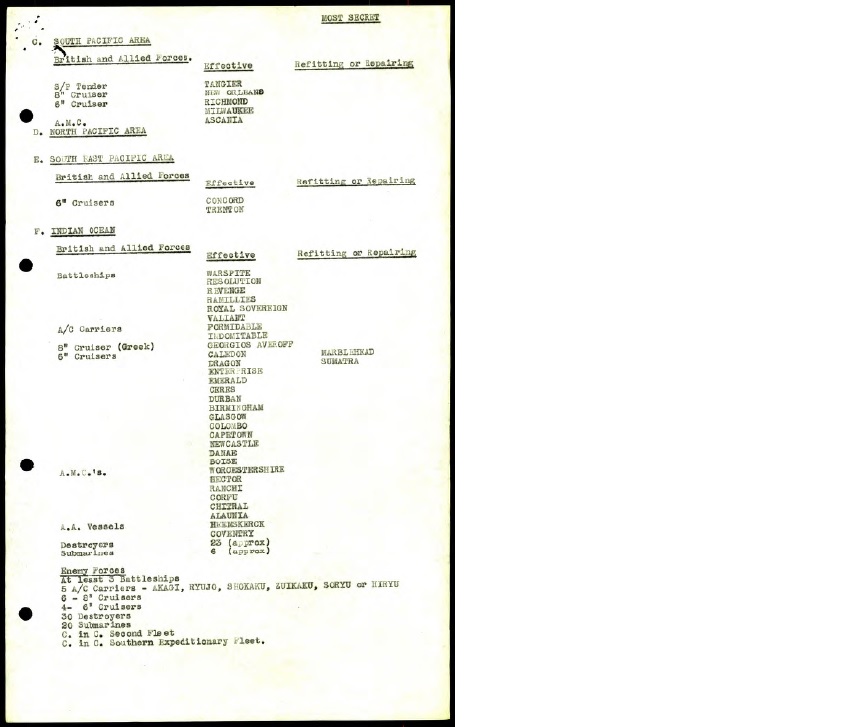

Royal Australian Navy – Daily Appreciation Report

Headed “Most Secret”, the following pages are taken from the April 1942 Royal Australian Navies Daily Appreciation Report file, for British and Allied Forces, in the Pacific and Indian Ocean.

Amongst the naval vessels listed are two AMC’s, the HMS Alaunia (operating in the Indian Ocean) and HMS Ascania (operating in the Southern Pacific), this extract is for the 12th April 1942, but both ships were operating in these theatres throughout that month.