The Battle of the Atlantic was the largest naval campaign in the Second World War, it began on the day war was declared by Britain and finished almost six years later.

During those six years, 2,426 British registered ships were lost, with a total tonnage of 11,331,933 gross tonnes. At least 35,000 merchant seamen died as a direct or indirect consequence of the war, together with another 5,000, who were taken prisoner. These statistics give the casualty rate for merchant seamen at an amazing 85%. The allied navies lost 175 warships and 72,200 sailors during those six years, while the German navy lost 783 U boats and 30,000 sailors.

In 1938, British merchant ships routinely employed seamen from all over the world and 27% of their crew were Chinese or from British India with a further 5% being Arabs, Indians, Chinese, West Africans or West Indians living in UK ports such as South Shields, Liverpool and Cardiff.

The Armed Merchant Cruiser (AMC) of the British Royal Navy was employed for blockade purposes or as escorts for convoys during the battle of the Atlantic providing protection against enemy warships. They had limited value because they lacked the warship’s armour plating and used local control of guns rather than director fire-control systems. The Admiralty requisitioned 56 intermediate British and Dominion liners, varying in size from 6,267 tons to 22,575 tons.

They soon proved no match for the German surface raiders that they encountered, HMS Rawalpindi was sunk by Scharnhorst and Gneisenau in November 1939, HMS Jervis Bay fell victim to Admiral Scheer in November 1940 and of the ships which engaged the German auxiliary cruiser Thor at different times during her first cruise, two were outfought and the third was sunk. Altogether 15 of the 56 were lost, 10 to U-boats. Churchill thought them ‘an immense expense and also a care and anxiety’ and by October 1941 most had been withdrawn for use as troop transports.

The armament provided to these AMC’s was varied, but six 6 inch (152 mm) naval guns with two High Angle 3 inch (76 mm) guns as secondary was usual.

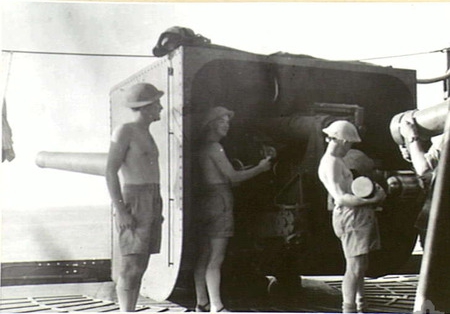

Loading a BL Mk VII gun during gun drill onboard HMS Laconia

The BL Mk VII 6 inch naval gun was fitted to most AMC’s including all of the former A Class liners. The BL Mk VII gun returned to loading charges in silk bags after it was determined that with new single-action breech mechanisms, a 6-inch BL gun could be loaded, vent tube inserted and fired as quickly as a QF or Quick Firing 6 inch gun, which it replaced. Cordite charges in silk bags stored for a BL gun were also considered to represent a considerable saving in weight and magazine space compared to the bulky brass QF cartridge cases.

The BL Mk VII 6 inch naval gun was first introduced on the Formidable class battleships of 1898 (commissioned September 1901) and went on to equip many capital ships, cruisers, monitors, and smaller ships such as the Insect class gunboat which served throughout World War II. The BL Mk VIII was sometimes fitted and was identical to Mk VII, except that the breech opened to the left instead of to the right, designed for use as the left gun in twin turrets.

The Starboard Mk VII gun crew onboard HMS Ausonia

Cleaning the Port Mk VII gun onboard HMS Ausonia

The secondary armourment 12-pounder 12 hundredweight, Mk V dual-purpose high-low angle 3 inch (76 mm) guns had a “monobloc” barrel made of a single casting. This type of gun was the main armourment for many smaller escort ships such as destroyers but on armed merchant ships, the dual-purpose high-low angle mountings allowed it to be also used as an anti-aircraft gun.

A trawler’s gun crew manning the Mk V gun of the type fitted to AMC’s.

Aboard an Admiralty Made Coffin

These are the memories of Jimmy Robert from Barra, in the Outer Hebrides, who served 4 years on-board the Armed Merchant Cruiser, HMS Ranpura as a Royal Navy Surgeon Lieutenant but his experiences apply to all the other 56 AMC’s.

The P&O liner Ranpura was on her way to Australia when war broke out. She was requisitioned by the Admiralty and found herself in Calcutta being fitted with armour plating and mounted with 6 inch guns. Her sister ships, Ranchi, Rajputana and Rawalpindi, were also taken over about this time.

I joined HMS Ranpura in Halifax, Nova Scotia, where she was one of the North Atlantic Escort Force on convoy duty. The ship’s company of about 400 men consisted of a few Royal Navy officers and ratings brought back from retirement.

Most of the other officers were Royal Naval Reserve (RNR) some of whom were taken over with the ship at the outset. There was a number of east coast fisherman, Royal Fleet Reservists (RFR) or volunteers, Jacks and Patience’s from Avoch, Buchan’s and Criggies from Peterhead being a few of them.

Many of the stewards, firemen, greasers, six Chinese carpenters, the Indian curry cook and an African laundry man, stayed with the ship as she entered war-time service.

The rest of us were young volunteers and members of the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve (RNVR). We were a happy ship not taking too serious a view of the strict naval discipline. Merchant ships crossing the Atlantic were first gathered in the Bedford Basin, the large inner harbour of Halifax.

Every week or so, 40 or more ships would sail out to be marshalled into nine parallel columns under the command of the commodore, a senior Royal Navy or Merchant Navy officer, sailing in one of the larger merchant vessels. We then took up station in the centre of the convoy, our main duties being to keep in touch with Admiralty and to afford some form of protection against surface attack by the German light pocket battleships which roamed these northern waters. Our chances of surviving such attacks were nil, but our resistance might possibly let the merchant ships scatter so that at least a few of them might get through to the UK.

Our 6 inch guns previously belonged to HMS Bonaventure built in the 1890s and were no match for the German weaponry. Once the convoy was halfway over, we entered the “killing zone” where the U-boats played havoc amongst the merchant ships. We were soon joined by a strong force of destroyers and corvettes which did well escorting the convoy until it reached the safety of home waters. Ranpura then left the convoy and turned north for Iceland to refuel, rest and to wait for a convoy outward bound for Halifax.

Sixty-six years ago almost to the day as I write this, we joined convoy OB 314 bound for Halifax. The anti-submarine escort, HMS Bulldog, a destroyer and several corvettes were still with the convoy. Almost as soon as we joined the ships the U-boats started to attack and two ships were torpedoed close to us, one quickly ablaze. It was heart-rending to hear the cries of the burned and injured crew. I hoped that they might be picked up by the rescue ship, one of the convoy being appointed each day for this duty. Sometimes, no sooner had they performed their act of mercy, than they themselves were torpedoed. We were under attack for three days.

On 9 May, the corvette HMS Aubretia had a very close contact on a U-boat. She dropped her depth charges which quickly brought up U110. HMS Bulldog immediately prepared to ram her when the conning tower opened and the entire crew abandoned ship. Bulldog sent over a party who went down into the submarine returning with many articles of equipment including the code books and the Enigma machine. The incident was treated as most secret in the hope that the German High Command would not learn of their important loss. Later, Winston Churchill declared that this affair proved the turning point of the war.

The very high loss of merchant ships had Britain nearly to her knees but after this, the U-boat menace gradually lessened and more essential foods and war supplies began to reach the UK again.

As more and better naval vessels were built, our type of ship was assigned to other duties such as trooping and we worked in the Indian Ocean. We returned to the UK to Invergordon where we acted as accommodation ship for several hundred Royal Marines practising beach landings in the nearby Moray Firth prior to the real thing on D-Day.

About 50 merchant ships were requisitioned to become Armed Merchant Cruisers (AMCs). Fifteen of those were lost to enemy action. No wonder that they were called Admiralty Made Coffins.

This short article would not be complete without mention of HMS Jervis Bay and the heroic fight of Captain Fogerty Fegan and his men against the much superior pocket battleship the Admiral Scheer. His actions allowed many of the merchant ship of convoy HX84 to escape before they themselves were sunk. Fogarty Fegan, who went down with his ship, was awarded a posthumous Victoria Cross.

Shortly after this, as we were setting off to link up with another convoy, news came through that another two AMCs had been lost. It was Sunday and as we stood at church service on the main deck singing. As the line “for those in peril on the sea” drifted away over the cold grey waters of the Atlantic I am sure there were more than I wondering whether our luck would hold.

I was proud to have served my time at sea in a Merchant Navy ship and to have known and respected so many of its fine brave officers and men.

Armed Merchant Cruisers

Between 1939 and 1940, 56 passenger liners, all twin screw vessels with a service speed of at least 15 knots, were requisitioned by the Royal Navy, as armed merchant cruisers. By the end of 1941, 15 had been lost and the Admiralty decided that they were too vulnerable for ocean escort work and they began to be withdrawn, although some were kept in commission until much later in the South Atlantic and East Indies. By January 1943, only 17 armed merchant cruisers were left, 6 in the South Atlantic, 8 in the East Indies and 3 in Australian and New Zealand waters. They had been reduced to 8 by January 1944 and by May 1944 only the damaged HMS Asturias remained, laid up in Freetown.

By this time, of the other surviving 40 vessels, 1 had been converted to an escort carrier, 1 to an auxiliary anti-aircraft ship, 2 to Depot ships, 4 to Repair ships, 8 to Infantry Landing ships, 2 to Headquarter ships and the remaining 22, to troopships, a obvious and successful role for ex-passenger liners. The Deport and Repair ships, of which HMS Ausonia was one, were later purchased outright and retained in the post war fleet.

As armed merchant cruisers, they were fitted with rudimentary fire control equipment and surface warning R.D.F. as it became available, and were generally armed with between six and eight First World War vintage, 6 inch guns. For anti aircraft defence, they had two, 3 inch guns and an assortment of light and heavy machine guns and a few even had an aircraft and catapult added. The best equipped of them all, HMS Corfu, was fitted with gunnery control R.D.F. and had nine 6 inch, four 4 inch, two 2 pounders, nineteen 20 mm guns and an aircraft and catapult.

The 15 Armed Merchant Cruisers lost were:

HMS Andania Sunk 16/06/40 by UA.1 South East of Iceland

HMS Carinthia Sunk 07/06/40 by U.46 West of Ireland

HMS Comorin Lost 06/04/41 by fire North Atlantic

HMS Dunvegan Castle Sunk 28/08/40 by U.46 West of Ireland

HMS Forfar Sunk 02/12/40 by U.99 West of Ireland

HMS Hector Total loss 05/04/42. Salvaged but eventually scrapped 1946

HMS Patroclus Sunk 04/11/40 by U.99 West of Ireland

HMS Jervis Bay Sunk 05/11/40 by Admiral Scheer North Atlantic

HMS Laurentic Sunk 03/11/41 by U.99 North West of Ireland

HMS Rajputana Sunk 13/04/41 by U.108 West of Iceland

HMS Rawalpindi Sunk 23/11/39 by Scharnhorst South East of Iceland

HMS Salopian Sunk 13/05/41 by U.98 North Atlantic

HMS Scotstoun Sunk 13/06/40 by U.25 North West of Ireland

HMS Transylvania Sunk 10/08/40 by U.56 North of Ireland

HMS Voltaire Sunk 04/04/41 by Auxiliary Cruiser Thor Mid Atlantic

The surviving vessels were converted as follows:

HMS Alaunia Converted to Repair ship 1944

HMS Alcantara Converted to Troopship 1943

HMS Antanor Converted to Troopship 1942

HMS Arawa Converted to Troopship 1941

HMS Ascania Converted to Troopship 1942 then Landing Ship Infantry 1943

HMS Asturias Laid up damaged 1944

HMS Aurania Converted to Repair ship HMS Artifex 1942

HMS Ausonia Converted to Repair ship 1942

HMS Bulolo Converted to Headquarter ship 1942

HMS California Converted to Troopship 1942. Lost 11/07/43

HMS Canton Converted to Troopship 1944

HMS Carnarvon Castle Converted to Troopship 1944

HMS Carthage Converted to Troopship 1943

HMS Cathay Converted to Troopship 1942

HMS Cheshire Converted to Troopship 1943

HMS Chitral Converted to Troopship 1944

HMS Cilicia Converted to Troopship 1944

HMS Circassia Converted to Troopship 1942. Landing Ship Infantry 1943

HMS Corfu Converted to Troopship 1944

HMS Derbyshire Converted to Troopship 1942 Landing Ship Infantry 1943

HMS Dunottar Castle Converted to Troopship 1942

HMS Esperance Bay Converted to Troopship 1941

HMS Kanimbla Converted to Headquarter ship 1943

HMS Laconia Converted to Troopship 1941. Lost 12/09/42

HMS Letitia Converted to Troopship 1941

HMS Maloja Converted to Troopship 1941

HMS Manoora Converted to Landing Ship Infantry 1942

HMS Monowai Converted to Landing Ship Infantry 1944

HMS Montclare Converted to Depot ship 1943

HMS Mooltan Converted to Troopship 1941

HMS Moreton Bay Converted to Troopship 1941

HMS Pretoria Castle Converted to Escort Carrier 1943

HMS Prince David Converted to Landing Ship Infantry 1943

HMS Prince Henry Converted to Landing Ship Infantry 1943

HMS Prince Robert Converted to Auxiliary Anti-Aircraft vessel 1943

HMS Queen of Bermuda Converted to Troopship 1943

HMS Ranchi Converted to Troopship 1943

HMS Ranpura Converted to Repair Ship 1944

HMS Westralia Converted to Landing Ship Infantry 1943

HMS Wolfe Converted to Depot Ship 1941

HMS Worcestershire Converted to Troopship 1943

Extracts from World Ship Society booklet “Conversion for War” by Dr Richard Osborne

British Armed Merchant Cruiser’s or AMC’s, were in the main comprised of the intermediate type of liner of around 15,000 tons, mainly steam and oil fired, they were also self sufficient in water. Fifty six ships were requisitioned across the world in 1939, fifty directly by the Royal Navy and the other six by Commonwealth navies, (3 by Canada and 3 by Australia).

AMC’s were principally requisitioned in UK ports, though some were taken in India, South Africa, Australia and Western Canada. Port of requisition was normally the fitting out port also, but not in all cases. Three different dates are quoted for the takeover of each ship and all are correct. They could be the actual date that the ship was requisitioned, the commissioning date, which for legal reasons was normally the date that fitting out commenced or the date that the initial fitting out was completed.

Armament had been laid aside at suitable ports, mainly in the UK but also at overseas bases, and consisted of a basic outfit of six, seven or eight, 6 inch guns and two 3 inch HA per ship plus a very simple director system that simply indicated the bearing and in most cases, the elevation on a “follow the dial” system. Normal method of mounting was to dispose the guns on the beam to give a broadside of four and chase fire of two guns.

Some ships were capable of fitting only six guns, in others it proved possible to fit one gun on the poop instead of the after pair economising on weight and weapons, there were also cases of five guns forward and three aft, two being on the centre line, but four guns on each beam was pretty standard. The vast majority of guns were late 1890 to early 1900 marks on the old P.III mounting, removed from battleship casemates in the main and were limited to 20 degree elevation and 14,000 yards range. This led to bitter complaint after early actions with raiders whose 5.9 inch although equally old, ranged beyond 14,000 yards so that the enemy simply opened the range and fired at will.

German and British armed merchant cruisers had one thing in common, the source of main armament. In the German case, the casemates of their pre-dreadnought battleships to a large extent furnished the 5.9 inch main armament, British weapons stemmed from a similar source, plus the older C Class cruisers of the 1914 era. However, there the similarity ceased for there were significant differences between the mountings of each service. In the German case either mounting was a more modern design, or had been updated so that the gun the German far outranged the British weapon. British mountings were in the main, the P.III and later P.VII versions, using the Mk. VII 6 inch gun, with a sprinkling of CP.XIV mountings later in the war. The original P.III elevated to only 14 degrees as did the P.VII and in both cases ranged out to 11,900 yards. This was increased to 14,200 when the elevation was increased to 20 degrees.

Initially most AMC’s were fitted with gun mountings which were all of the same type and all had standard shell and charge. A partial re-armament and re-ammunitioning took place to provide a gun range comparable to that of their opponents; it was normally confined to the two forward guns, one on each beam, or three where there was a centreline gun forward. Most mountings were unshielded initially even when there was gross exposure to weather as in the case of guns mounted right forward or aft. This lack was due as much to the provenance of the mounting (battleship casemates) as to lack of thought. Where shields were fitted it was noticeable that they were of the pattern of that found in the early C Class cruisers. Later in the war some AMC’s received CP.XIV gun mountings which, in all probability, had been removed from later C Class cruisers when they were converted to AA ships. Some of the early mountings, were it is true, fitted with a squared off shield at a later date and these were similar to the later C Class shields in style.

Various attempts were made to improve AMC gunnery capability by either increasing mounting elevation or fitting mountings with greater elevation, improved shell and super charges to produce greater propellant power. Thus two 6 inch Mk.VII were replaced by 6 inch Mk.XII on 30 degree mountings in Ausonia in May 1941. With super charges issued, a range of 19,500 yards could be achieved at 20 degrees elevation and with 100 lbs 6 inch shell. Ant-aircraft armament was restricted to two 3 inch HA guns and machine guns, totally inadequate but all that was available at the time. As the war progressed and supplies became available, surviving ships began to mount the 20mm Oerlikon gun and occasionally a pair of single 2 pdr. Guns (Alaunia).

Initial fitting out was dictated by the time taken to strip the ships and fit guns etc, later work was carried out as ships refitted or repaired and there was a drastic reduction of superstructure to reduce top weight. Thereafter, whenever in port for short refits these ships were further militarised by progressive elimination of mercantile top hamper, enlargement of the bridge, installation of radar, rangefinder and searchlight platforms and light AA guns. Nevertheless there was a need for quantities of ballast and in the main some 2,000 tons plus was shipped in almost all ships principally in the form of rock ballast. Furthermore, as the number of wartime alterations and additions accrued, so did the weight of the ballast shipped.

By naval standards, the AMC’s had an almost total lack of watertight subdivision and in an effort to provide a measure of buoyancy in the event of damage below the waterline “buoyant cargo”, in the form of empty sealed drums, was stowed. Again this was increased progressively as time in port allowed. Ships carried as many as 30,000 of these and ships fitted out in the Far East stowed, in some cases, bundles of rattan in lieu of drums.

Magazines were fitted in the lower holds with simple hoists to the upper deck and manual transfer of shell and charge to the beam positions. The magazines and hoists were protected by mild steel plate 1 inch to 11/2 inch for splinter protection. In one or two cases, wood of unknown thickness was substituted but it must have been considerable to have had even a minimal effect.

In all cases a small number of depth charges, usually 15, were carried in chutes, to provide a deterrent to keep down a submarine after a sighting, while the ship made her escape. Some ships also carried two throwers, in which case the depth charge outfit went up to 30, but as no ASDIC was ever shipped, it can never have been contemplated that there was an A/S capability, only a deterrent after sighting or an abortive attack.

The number of boats ships carried was reduced progressively during the war so as to conform to the total complement of the ships as AMC’s as well as saving top weight. In many cases one or two large motor cutters or pinnacles were carried in chocks on deck for use as harbour craft as well as boarding duties in connection with contraband control at sea.

The wireless fit was unaltered from that found in merchant service as by nature of their trade; the ships had sets of comparable power and range to most convoy escort vessels, indeed greater. Reports of proceedings speak of missed signals, but this appears to have been due more to local conditions or operator problems rather than inadequacy of equipment and was of fairly rare occurrence.

The AMC’s began to be fitted with radar in 1941. Typical installations included Type 286 air search radar at the foremast head and Type 271 surface search radar in a weatherproof lantern mounted on a lattice tower on the bridge. Surprisingly, the AMC’s seem to have been relatively high in the list of priority for receipt of the Type 271 set, presumably because it was essential for convoy operations, especially station keeping at night.

Fuel stowage’s and hence range increased as the war progressed. It is unlikely that further capacity was built into the ships so either the official records were understated initially or more likely, increased ballasting, etc permitted the use of a greater portion of the total capacity.

The advent of convoys at the outbreak of war brought a new duty for the AMC. The principle of convoy was that the conduct of it was vested in a Commodore borne in one of the merchantmen; he was frequently a retired Flag Officer, or a competent master mariner. These latter did not exist in the sense of convoy experience in 1939 nor were merchantmen always able to handle the communications traffic or carry the necessary coding material. Furthermore, the absence of naval escort for much of the voyage deprived the convoy of its “whipper in” and general supervisory presence that the Commodore could normally call upon. Hence all North Atlantic eastbound convoys and their feeders from Bermuda were accompanied by an AMC as “Ocean Escort”. While it is true that there was a minimal escort capability, the main purpose was as previously stated. By late 1941 this practice had been abandoned in North Atlantic convoys but was continued in the SL convoys between Freetown and the UK where the R.N. escort changed frequently, so that the AMC provided a degree of continuity. The advent of the through escort on the North Atlantic and the increasing expertise of the merchantmen and masters removed the need in due course. However, in the Far East and South Atlantic the use of AMC’s as escorts continued long into the war due to sheer lack of suitable escorts.

AMC’s were very hard worked both in the initial Northern Patrol in the first year of the war and elsewhere. Thus, a Halifax based AMC could expect to take a convoy east until met by the UK based escort and then return to Halifax, a round voyage of some 26 days followed by 4/5 days in port. A later development was to hand over the eastbound convoy, go north to patrol the Denmark Strait or Greenland passage, fuel in Iceland and return to |Halifax with the latter part of an ON convoy, a total of 30 to 32 days at sea. Some AMC’s were based at Bermuda to handle the feeder BHX convoys and having met the HX section they would return to Bermuda. Usually after three such runs they took in the HX portion of the convoy and the HX AMC went to Bermuda for a “rest” in warmer climes. In the summer of 1940 and again in 1941, some Halifax based ships sailed directly to Bermuda, the purpose being to freight water to the island.

By comparison Freetown based ships of the South Atlantic Station maintained a patrol off South America and in the South Atlantic generally. 100 days at sea was not uncommon with a 24 hour fuelling period at Rio de Janeiro, Montevideo, Buenos Aires or the Falklands every thirty days. East Indies and Far East ships were employed on contraband control and merchant blockade of know enemy merchantmen in the early days, later raider patrols and convoy escort also involved very long passages.

Generally, the ships were manned seaman wise by recalled reservists and “Hostilities Only” ratings and commanded and officered by retired R.N. officers and R.N.V.R. junior officers. However, where the merchant complement included R.N.R. officers, these were usually retained on board, frequently with the master becoming Navigating Officer. Engine room and catering/purser staff to the AMC’s requirements were almost always the original complement or part of it. Merchant Navy personnel signed either T124 or T124X articles; these were in effect ships articles with the State rather than the Company and placed the signatory in uniform as a combatant under the Naval Discipline Act while retaining his pay and leave entitlement from civilian life and his obligations for pension payments and the like. T124 was for the ship, T124X for the duration of hostilities or until required, thus, if the ship paid off from R.N. service the T124 man reverted to civilian articles, the T124X man could be drafted / appointed elsewhere.

The demise of the AMC was due to various factors. By 1942 the manpower problem was becoming acute, as was the lack of troop carrying space and refrigerated cargo capacity and the AMC came into all three classes. The Ministry of War Transport pressed for their release to merchant service, the navy wanted the crews and finally the AMC was a large and vulnerable target as shown by the losses in their numbers.

Unfortunately there was a third factor involved, the lack of cruisers. Commanders in Chief South Atlantic and East Indies fought to keep their AMC’s, not because of the ships themselves but because of the sheer lack of replacements. New construction did not keep pace with the need for more ships and replacement of losses and C in C East Indies went on record saying that if his AMC’s were withdrawn then convoys must sail totally unescorted.

A similar problem arose in Freetown where there was no possible replacement for the AMC’s patrolling the Atlantic Narrows against blockade runners except the future possibility of French cruisers that would not be under British operational control.

Hence some AMC’s remained on duty long after anyone desired it simply through lack of an alternative. The AMC had a cruising capacity approached only by a County Class cruiser in the main and consequently replacement had to be by a large cruiser, if at all and these were in short supply.

Cunard ‘A’ Class Liner details

HMS Alaunia

Tonnage 14,030 gross

Launched 07/02/25

Armament 1939 Eight single 6 inch guns, two single 3 inch guns

Requisitioned 25/08/39 as AMC, repair ship 1944

HMS Andania

Tonnage 13,950 gross

Launched 01/11/21

Armament 1939 Eight single 6 inch guns, two single 3 inch guns

Requisitioned 05/09/39 as AMC, sunk 16/06/40 after being torpedoed

HMS Ascania

Tonnage 14,013 gross

Launched 20/12/23

Armament 1939 Eight single 6 inch guns, two single 3 inch guns

Requisitioned 05/09/39 as AMC, 29/10/42 as MWT troopship, as LSI(L) 1943.

HMS Aurania

Tonnage 13,984 gross

Launched 06/02/24

Armament 1939 Eight single 6 inch guns, two single 3 inch guns

Requisitioned 30/08/39 as AMC, repair ship 20/10/41

Renamed HMS Artifex 01/12/42

HMS Ausonia

Tonnage 13,912 gross

Launched 21/03/21

Armament 1939 Eight single 6 inch guns, two single 3 inch guns

Requisitioned 02/09/39 as AMC, repair ship 27/03/42, completed April 1944

HMS Antonia

Tonnage 13,867 gross

Launched 11/03/21

Requisitioned 02/10/40 originally as AMC, but changed to repair ship 27/03/42

Renamed HMS Wayland 01/08/42